by William Moon

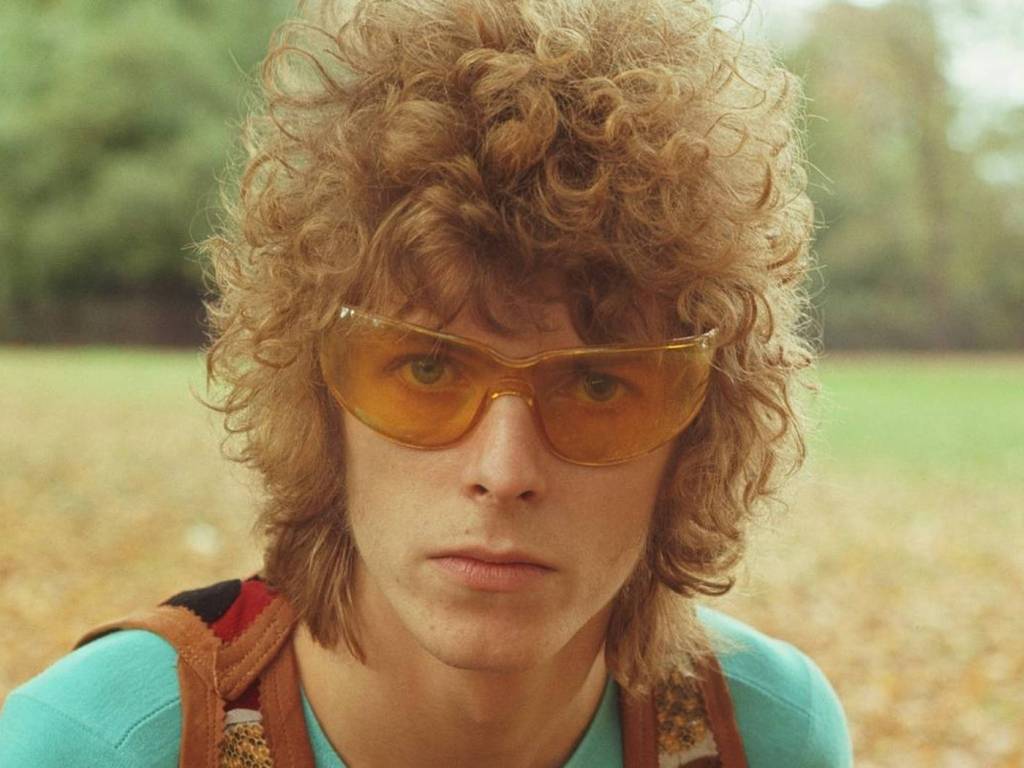

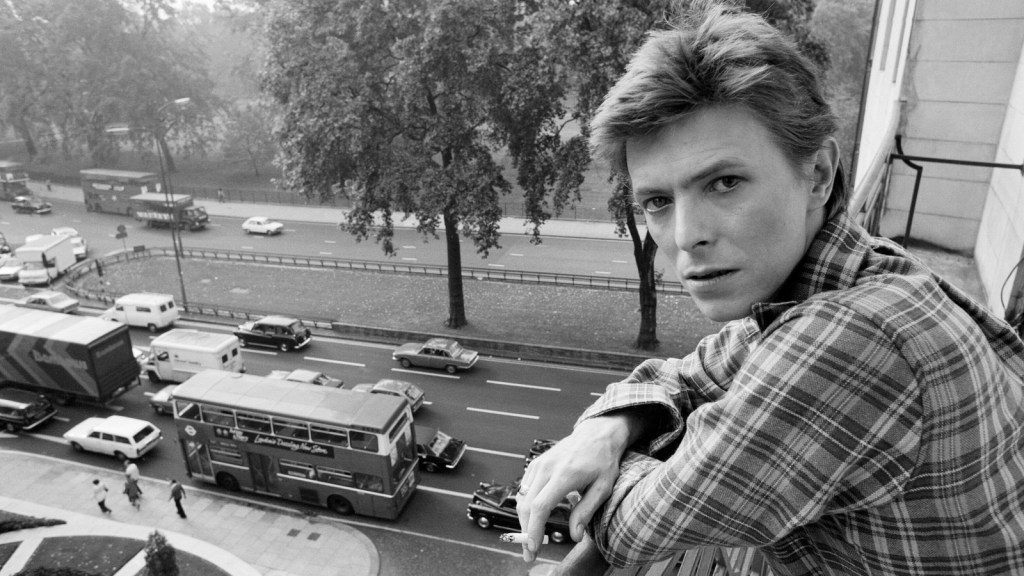

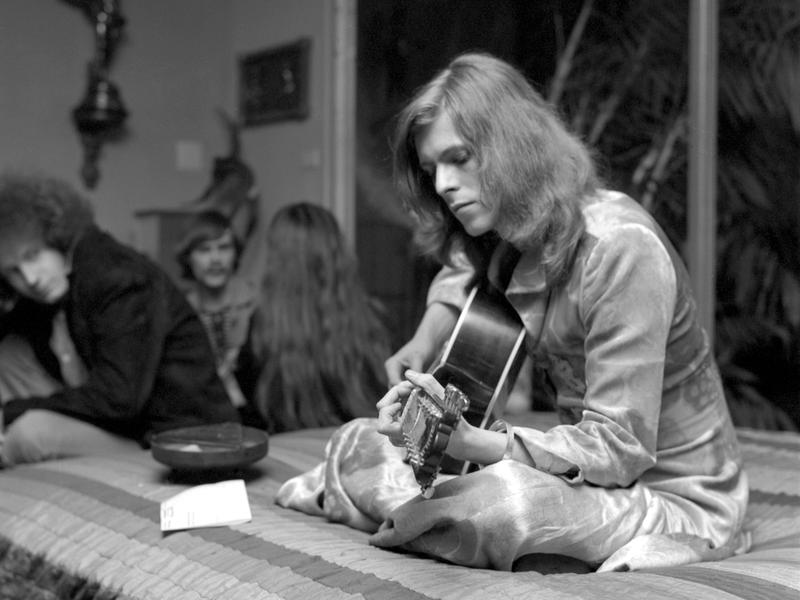

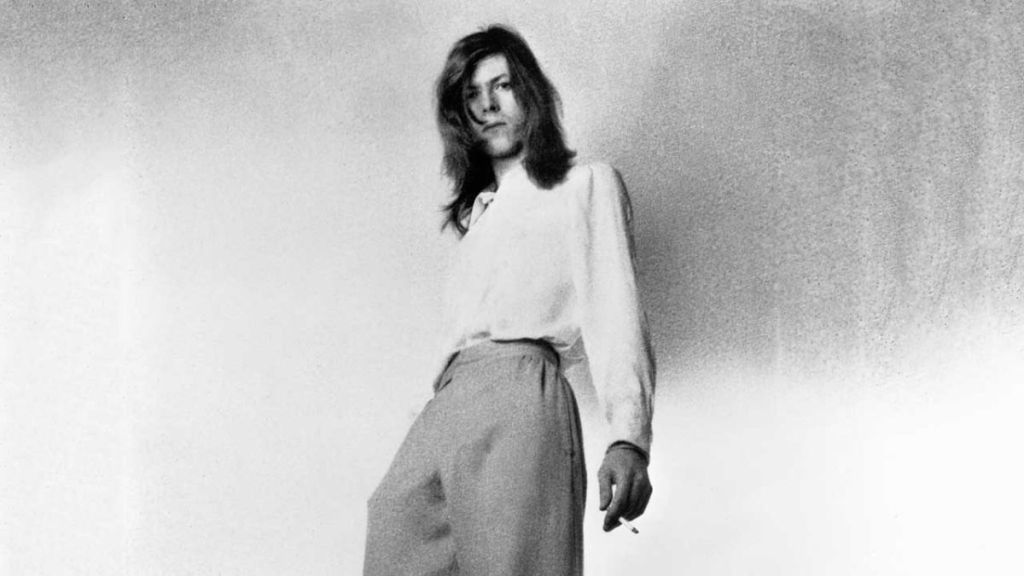

We lost David Bowie over seven years ago now, which feels impossible until you remember how little meaning time has had in the intervening years (too busy flexing and wanking, I suppose). The recent appearance of his Queen duet “Under Pressure” in the award-nominated film Aftersun sent me into a Bowie place, and digging into a possible top 100 list gave me the chance to really explore his catalog and listen to some stuff I hadn’t heard before. Plus it was fun to scour for as many rare tracks as I could.

Given the modest beginnings of this project, I didn’t necessarily have any notable anniversary in mind when I started this process, but Google tells me we’ll hit the 50th anniversary of the underrated Aladdin Sane, the 40th anniversary of the megahit Let’s Dance LP, and the 30th anniversary of 1993’s Black Tie White Noise all in April, while we passed the 10th anniversary of The Next Day‘s release in March. Clearly the man liked his springtime releases, so if you like round-number milestones, there are plenty to choose from.

A quick note on the methodology here – I’m sticking with Bowie originals, so no covers (unless it’s Bowie covering himself or a song he wrote for someone else, which he did often). Also we’re focusing on official studio releases, not live cuts or bootlegs or whatever. For collaborations, he has to be credited on the release, so Mott the Hoople’s version of “All the Young Dudes” is out, for example. (Bowie’s own recording of it obviously counts.) In the case of songs with multiple official studio releases, I’ll make a point to designate which one I’m ranking.

With all that said, let’s dance.

100. “The Supermen” (1970, The Man Who Sold the World)

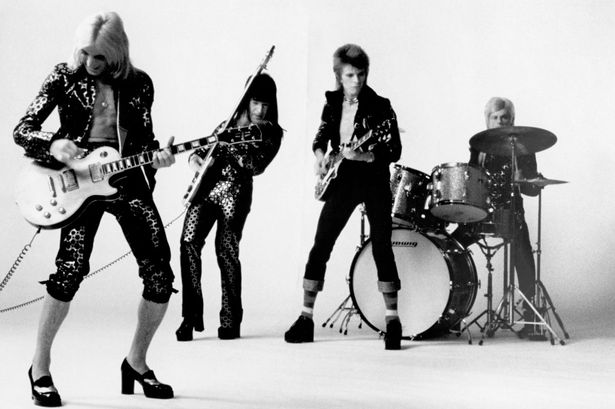

The closing track on Bowie’s third LP, “The Supermen” carries the doomy sound of the record to its fullest with ominous backing vocals and a thumping rhythm section provided by bassist/producer Tony Visconti and future Spiders from Mars drummer Woody Woodmansey. Bowie was in a Nietzsche phase at the time, with the German philosopher inspiring songs all over both this record and 1971’s Hunky Dory. Guitarist Mick Ronson (who, along with Woodmansey, was making his first credited appearance on a Bowie record) contributes some sharp guitar work, particularly in the track’s second half. The band generally sounds a little tighter on this number than they do on many of the other cuts from the album, and the song also benefits from a sludgy guitar riff that Bowie says was given to him by Jimmy Page years before either man would reach stardom.

99. “Can’t Help Thinking About Me” (1966, single)

The first song released under the David Bowie name, “Can’t Help Thinking About Me” was recorded with his then-backing band the Lower Third late in 1965 and released in January 1966. The song is a rewrite of the rejected earlier single “The London Boys” and is the best song from Bowie’s pre-“Space Oddity” period. Like his other releases during these years, the single flopped, though an overt attempt at rigging the chart by Bowie’s manager Ralph Horton did see it reach Melody Maker‘s Top 40. (It was also Bowie’s first ever American release, where it also flopped). The influence of mod-era bands like The Who and The Kinks is extremely clear, with Bowie paying tribute to those groups and other contemporaries with his Pin Ups covers album in 1973. Simple as it is, there’s something undeniably catchy about this one.

98. “Wild Eyed Boy from Freecloud” (1969, David Bowie)

Bowie’s sophomore record, officially self-titled but also known as Space Oddity and Man of Words/Man of Music, is decidedly a mixed bag. Combining elements of formal ’60s pop with folk music and some foreshadowing of the directions Bowie would soon take, the 1969 record is an interesting time capsule of a developing artist. This track, which was issued as the B-side of Bowie’s breakthrough “Space Oddity” in most markets, leans heavily toward the sound of highly produced ’60s British pop songcraft. A lush orchestral arrangement dominates the track, which is not a sound the singer would return to often in his career if at all, but there’s certainly an air of drama here. Lyrically the song is about Bowie’s struggle with an identity as a performer, while musically the song may or may not feature minor contributions from an uncredited Mick Ronson, which, if so, would mark his first collaboration with Bowie.

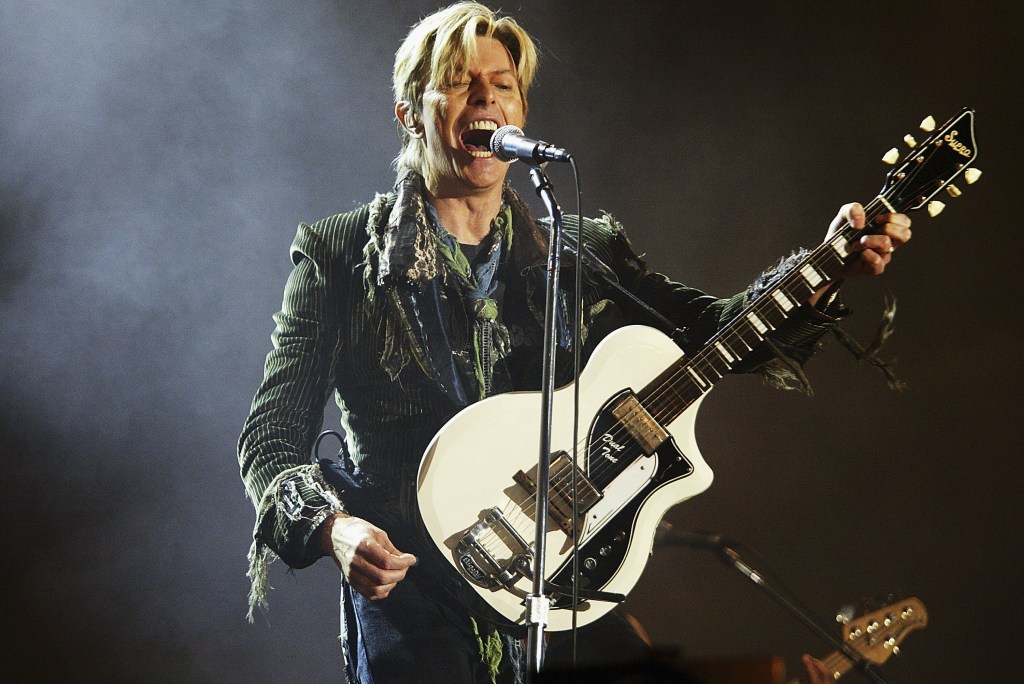

97. “Reality” (2003, Reality)

2003’s Reality would be Bowie’s last proper album release for a full decade, though we obviously didn’t know that at the time. Following up the previous year’s Heathen with an album that felt very in-step with the predominant alt-rock sound of the time, Reality also rocks a fair bit harder than its predecessor. That’s particularly notable on the title track, which has a frenetic pace and harkens back somewhat to the sound of Bowie’s side project Tin Machine from over a decade before. Lyrically, the song again deals with concepts of identity, but as opposed to “Wild Eyed Boy from Freecloud”, here Bowie tackles that concept from the standpoint of a man who’s older, more successful, but perhaps facing up to reality for the first time in some ways.

96. “Dead Against It” (1993, The Buddha of Suburbia)

The Buddha of Suburbia is a unique record in the Bowie catalog. Released with little fanfare about seven months after the commercially successful Black Tie White Noise, the album is nominally a soundtrack to the BBC’s television adaptation of Hanif Kureishi’s novel of the same name. As it played out, only the title track appeared in the show, while the rest of the album came together from Bowie’s impressions of the novel and exists mostly as its own separate thing. Bowie himself cited it at least once as his favorite record of his own in spite (or perhaps because) of the relative obscurity it quickly fell into upon release. Musically wide-ranging, the strongest track on the LP is “Dead Against It”, a spritely new wave-style jaunt that exists in the space between, say, New Order’s later material and several ’90s bands whom New Order inspired (The Dandy Warhols, for example). Despite the ominous title, this is arguably the most upbeat song in Bowie’s discography.

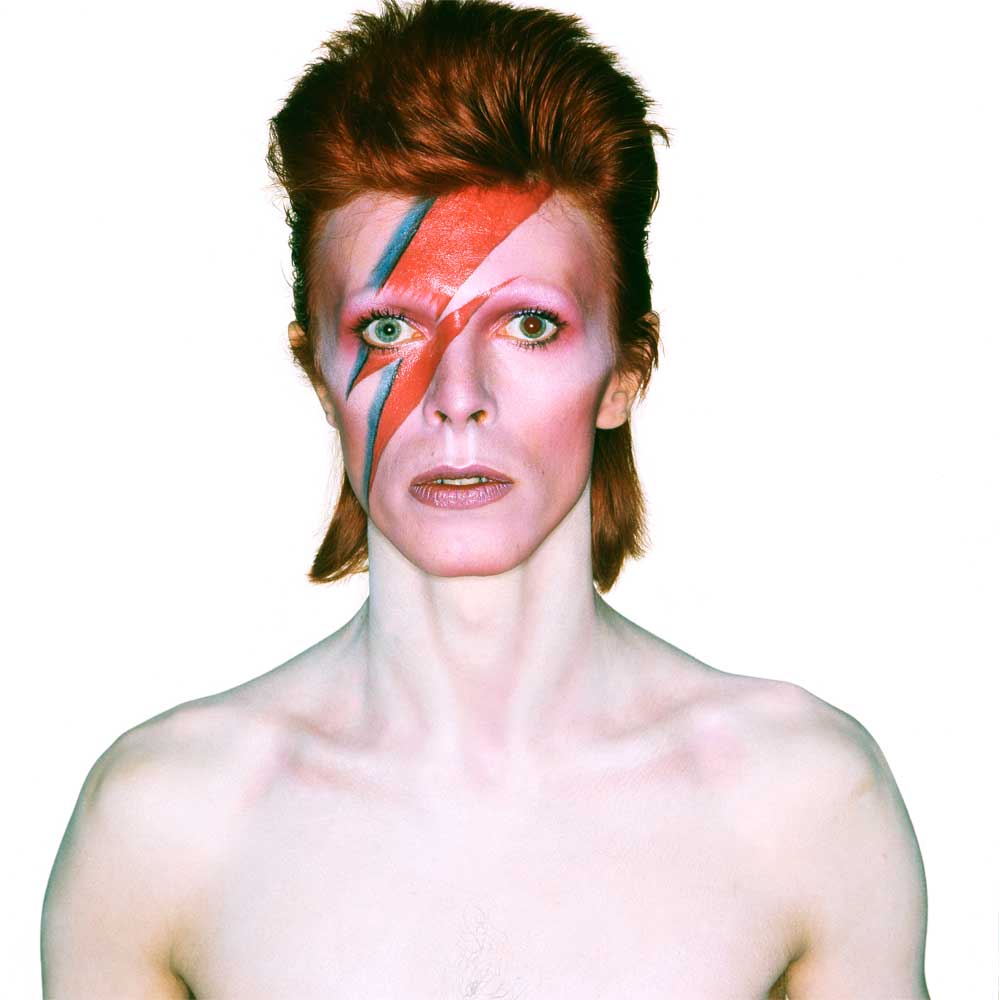

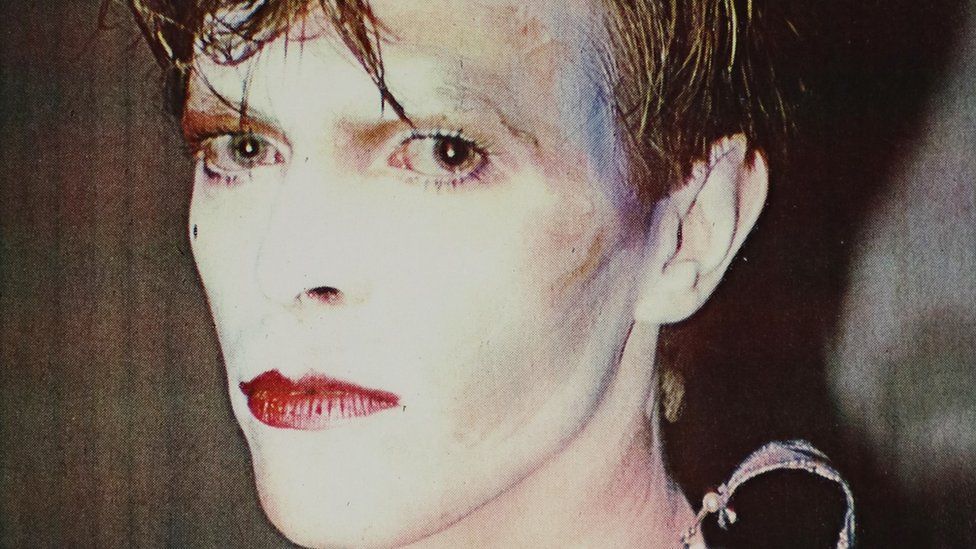

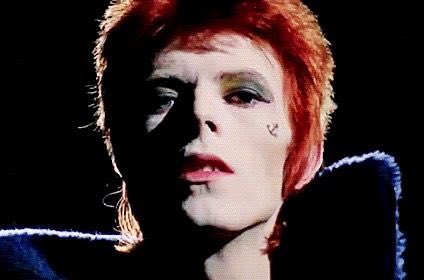

95. “Aladdin Sane (1913-1938-197?)” (1973, Aladdin Sane)

Probably the most initially repellent song on this list, the title track to Bowie’s 1973 Ziggy Stardust follow-up is dominated from front to back by jazz pianist Mike Garson. Garson entered Bowie’s orbit for the first time on this album, and the duo collaborated repeatedly afterwards. As for this song specifically, Garson originally contributed more conventional piano work, but Bowie rebuffed those efforts and instead asked for something particularly avant garde. The result is what you hear on record, which only grows more bonkers as the track progresses. Lyrically, the song also introduces Bowie’s new persona, a variation on his established Ziggy alter ego, while the parenthetical title nods at the singer’s belief in a coming third world war (1913 and 1938 being years in the lead-up to World Wars I and II respectively). This record would mark the beginning of a dark period for Bowie personally, and this song somewhat presages that.

94. “Beauty and the Beast” (1977, “Heroes”)

The opening track of “Heroes”, the second of Bowie’s Berlin albums, “Beauty and the Beast” lurches menacingly out of the gate, bringing back many of the German-inspired synth sounds of Low while prominently introducing the newest key collaborator in Bowie’s orbit, long-time King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp. King Crimson was broken up at this point, and Fripp had worked previously with Brian Eno prior to Eno’s seminal work with Bowie on Low. There are other tracks that feature Fripp more prominently, but this was a strong starting point for a fruitful musical partnership. Lyrically, the song is exceedingly dark and has been taken as a reference to Bowie’s coke-inspired mood swings from his pre-Low dark period. A strong opener to a strong album.

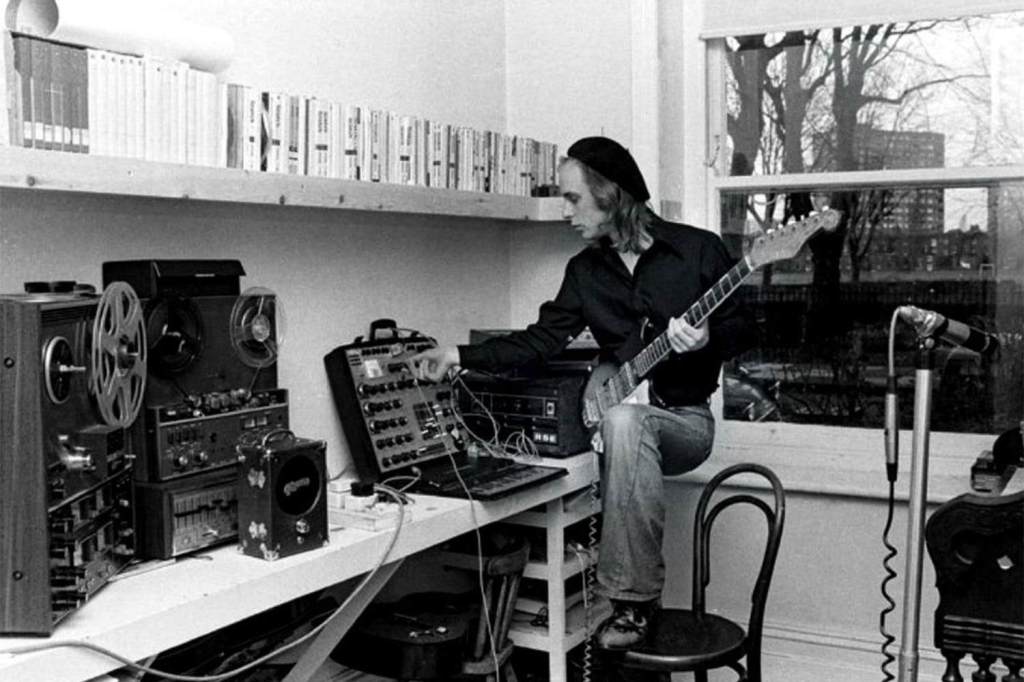

93. “The Voyeur of Utter Destruction (as Beauty)” (1995, Outside)

Outside is an absolutely wild record. Just skimming the Wikipedia page on it should give some clue as to how exactly nuts the whole thing was. Bowie reconnected with prominent ’70s collaborator Brian Eno, and a group of disparate past Bowie side players like Mike Garson, guitarist Reeves Gabrels, and bassist Erdal Kizilçay worked with the duo to produce a long, dense, often baffling Twin Peaks-inspired concept album (Bowie had appeared in 1993’s Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me in a particularly strange role). The album is often dismissed as an experiment with industrial music, though that style isn’t nearly as pervasive on the record as casual observers seem to think. And while it has some brutal lows (all of the spoken-word “Segue” tracks are debacles), there are some impressive highs as well. “The Voyeur of Utter Destruction” is one such high point, a track sung from the perspective of the story’s apparent villain against a hypnotic, atmospheric ’90s-style funk beat that handles that genre better than any of the drum-and-bass tracks on Bowie’s forthcoming Earthling record.

92. “Julie” (1987, single)

After taking a critical drubbing during his mid-’80s pop megastar phase, Bowie attempted to course-correct by bringing his music back to a more straightforward rock sound, only to bottom out with 1987’s lamentable Never Let Me Down. The forgettable pop stylings of much of his output from this era still pervade the record, and the record and its associated singles neither recaptured the chart success of Let’s Dance or Tonight, nor did they win back any critics or fans who had largely tuned out over the previous years. Which makes it strange to think that easily the best, catchiest, and most on-mission song recorded for the album was ultimately left off of it. “Julie” is immediately engaging, hooky, and refreshingly direct, seemingly everything Bowie was hoping to achieve with this project. How it got relegated to the B-side of the “Day-In Day-Out” single is anyone’s guess.

91. “Red Money” (1979, Lodger)

The closing track on Lodger, “Red Money” is an example of how that record shifted away from the sounds of its Berlin Trilogy predecessors and laid the groundwork for where Bowie would go next with the following year’s Scary Monsters. Co-written by guitarist Carlos Alomar, who’d been with Bowie since 1975’s Young Americans, a shuffling new wave-type beat is the backdrop for Alomar and future King Crimson member Adrian Belew’s guitar work, along with a memorable vocal arrangement. (Also no Brian Eno, who had been so influential on the first two Berlin albums and on many of the earlier tracks on this record.) Typically opaque, Bowie commented that the lyrics are about responsibility, but however you read its intent, the song shows an artist evolving into his next form.

90. “Cracked Actor” (1973, Aladdin Sane)

One of the scuzziest songs of Bowie’s career, “Cracked Actor” oozes ’70s LA sleaze from every note. Mick Ronson’s guitar work is particularly heavy, and the track is one of the clearest examples of the American influence on Aladdin Sane. Bowie’s growing fixation on the sound of The Rolling Stones during this period is also apparent here, and it would resurface on many of the glammier numbers on 1974’s Diamond Dogs. The song’s title has also followed Bowie through his career, partly because of his tendency to refer to himself as “the actor”, but largely because of the BBC documentary of the same name that first aired in 1975. Commercially unavailable still to this day, the program provided a fairly unvarnished peek into Bowie’s drug-addled mid-’70s mental state.

89. “Hang on to Yourself” (1972, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars)

An up-tempo number from Ziggy, “Hang on to Yourself” had originally been recorded by Bowie’s short-lived Arnold Corns project in early 1971, but that group fizzled out pretty quickly and Bowie went on to record Hunky Dory. The song, along with “Moonage Daydream” and “Lady Stardust” (which was never released by the band), found a second life after an updated version was released as part of Bowie’s breakthrough record the following year. The Spiders’ version combines glam-rock preening, some memorable Mick Ronson guitar lines, and a lead vocal that features some almost proto-punk stylings.

88. “Bombers” (1971, single)

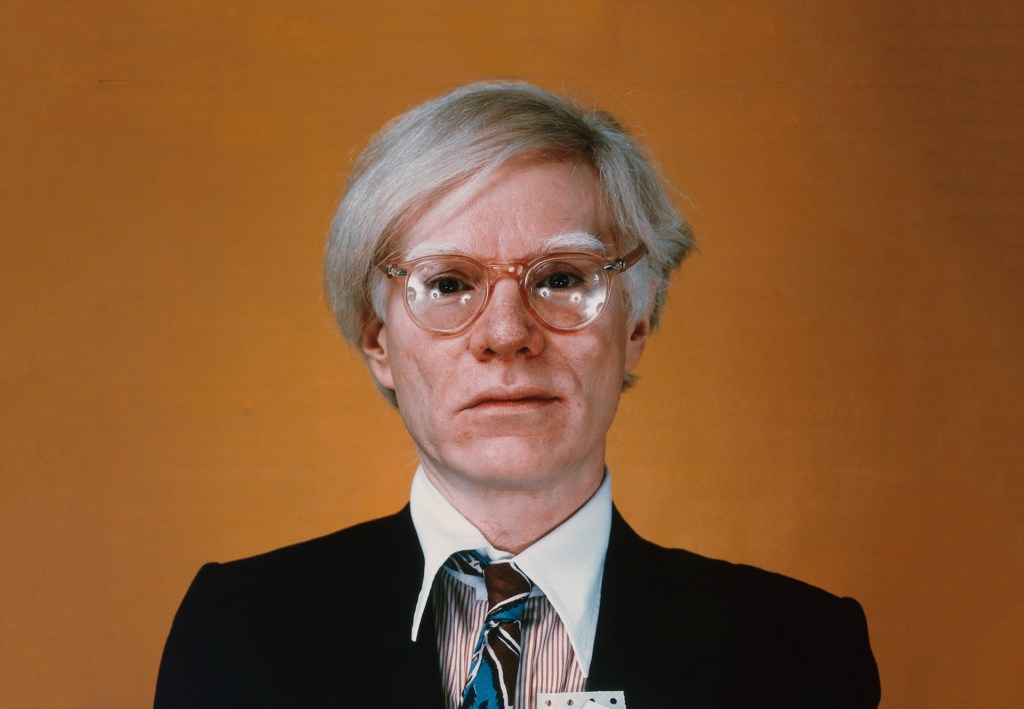

Written for 1971’s Hunky Dory and only replaced at the last minute (by a cover of Biff Rose’s “Fill Your Heart”), “Bombers” was instead released as promotional single in the US only. (Many existing mixes of it keep the studio-chatter segue into “Andy Warhol” that you hear on the album). The track is in keeping with the bright, poppy vibe of its parent record, but Bowie here does the classic maneuver of layering some pretty apocalyptic lyrics underneath a cheery veneer. This was quite a common trick for him during this period, as references to an impending world war and/or evolution of humanity into a new species are scattered across much of his early-to-mid-’70s output.

87. “Crystal Japan” (1980, single)

Mark Bowie down as one of many Western celebrities to have filmed an obscure-ish commercial in Japan. An instrumental he’d worked on while recording Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps), “Crystal Japan” was yet another track the artist decided to remove from an album at the last minute, opting instead to go with “It’s No Game (No. 2)” to close the record. Unlike other instances, though, this one makes sense as the piece, an ambient instrumental very reminiscent of his Berlin work, maybe doesn’t quite fit its parent album’s vibe. Instead Bowie used it as backing music for a Japanese shōchū commercial, with the track then being released as the A-side of a single over there. The release became prized among Bowie superfans in the UK, with the artist making a point to include the track as the B-side to the “Up the Hill Backwards” single so it could be easier to find.

86. “Velvet Goldmine” (1975, single)

One of the most overtly glam-rock songs of Bowie’s career, “Velvet Goldmine” was left off of 1972’s Ziggy Stardust album and not officially released until 1975, when it was one of the B-sides to a re-release of “Space Oddity”. By this time, Bowie had left his glam period behind, but the track quickly became a fan favorite and later became seen as emblematic of the entire glam rock genre. So much so that filmmaker Todd Haynes used it as the title for his 1998 film about the era. (Haynes asked Bowie for access to his back catalog, but Bowie refused, leaving the film the rely on Bowie pastiches instead of his actual music.) The song features some of the most salacious lyrics of Bowie’s career, but mixes them into a track that alternates glammy verses with a cabaret-like refrain, broken up briefly by a memorable guitar break from Mick Ronson.

85. “Blue Jean” (1984, Tonight)

After the runaway success of the previous year’s Let’s Dance album and accompanying singles, Bowie found himself feeling the need to hold on to a new audience. The problem was the extensive Serious Moonlight Tour had eaten up most of the time between album releases, and Bowie struggled for material. As such, “Blue Jean” and “Loving the Alien” are the only songs on the record solely written by the artist, and it’s no surprise that they’re the two strongest tracks. “Blue Jean” is undeniably catchy, something many of the other songs during Bowie’s pop-star phase simply aren’t, and while there isn’t a great deal of musical or lyrical heft here, hearing him excel as a pure pop singer/songwriter has its own charms.

84. “Andy Warhol” (1971, Hunky Dory)

It should come as no surprise that Bowie was a big admirer of pop-art icon Andy Warhol, but you would’ve thought the pair were closer than they actually were. Bowie wrote this track for the partly Americana-inspired Hunky Dory and actually got a chance to play it for its subject during a visit to Warhol’s Factory a few months before the album was released. Warhol listened to the song and then quietly walked out (in keeping with his often minimalist reactions), leaving Bowie unsure of his impression of the song. (A mutual friend later claimed that Warhol hated it.) Despite that, the track is one of many highlights on Hunky Dory, typifying both the record’s playful tone and its debt to many of Bowie’s American inspirations, particularly Warhol, Bob Dylan, and Lou Reed.

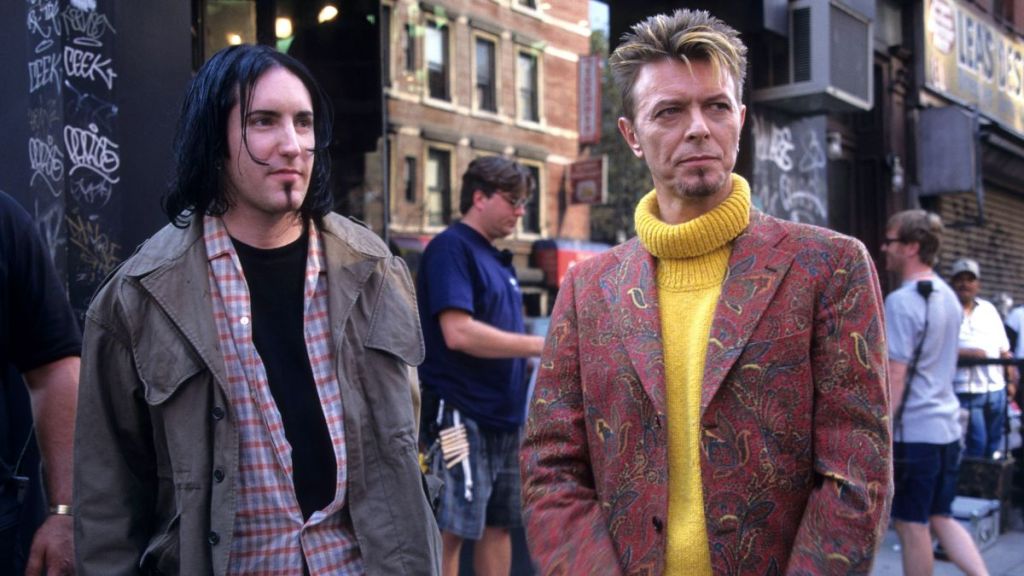

83. “I’m Afraid of Americans” (1997, single)

Originally written and recorded for 1995’s Outside, “I’m Afraid of Americans” went through several permutations. The 1995 version was included on the soundtrack to that year’s hilariously terrible Showgirls. Unsatisfied with that version, Bowie reworked the song for 1997’s Earthling, with it retaining Outside‘s industrial influence. That version is better than the original, but better still is the Trent Reznor remix that was later edited into the track’s single release. Reznor actually crafted multiple remixes for the maxi-single, one of which features Ice Cube, but the most memorable is the crunchy V1 mix. Reznor also appears prominently in the song’s music video, as he and Bowie continued their partnership following the Outside Tour. It’s very ’90s, but this foray into industrial has aged better than many of Bowie’s other genre flirtations from that decade.

82. “The Next Day” (2013, The Next Day)

While it can be easy to lump Bowie’s penultimate record, 2013’s The Next Day, in with its successor, 2016’s Blackstar, sonically it’s more akin to 2003’s Reality, his previous studio album. (Health issues incurred on the A Reality Tour had quietly pushed the artist into semi-retirement.) Similarly to the banger of a title track found on Reality, the title track here is even more of a rocker, with Bowie blasting out defiant lyrics laced with religious overtones. An even more religiously-themed video starring Gary Oldman and Marion Cotillard accompanied the song, the gruesome imagery of which (combined with the lyrics) made Bowie the target of ample criticism from many Christian groups. While making Bill Donahue mad would be enough for the track to be a win, the song itself is also just fiery and good, the most memorable piece from that album.

81. “Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps)” (1980, Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps))

A blistering, noisy piece, the title track to Bowie’s 1980 commercial comeback (after the creatively strong but commercially middling Berlin Trilogy) is dominated by Robert Fripp’s jagged guitar work. By this point, Fripp was soon to revive King Crimson (and bring fellow Bowie collaborator Adrian Belew along for the ride), but the sound of this track owes more to the English post-punk group Joy Division, who themselves were heavily inspired by Bowie. Dennis Davis pounds away at the drums underneath Fripp’s shrieking guitar work and Bowie’s darkly romantic lyrics. Just as with “It’s No Game (No. 1)”, it’s easy to detect a proto-industrial sound here, which makes the seemingly incongruous Bowie-Trent Reznor pairing 15 years hence seem not so incongruous after all.

80. “Amazing” (1989, Tin Machine)

In a career full of Bowie zigging (or Ziggying) when expected to zag, Tin Machine may be the oddest duck of them all. A band fronted by Bowie and featuring noise-rock guitarist Reeves Gabrels and the rhythm section of Tony and Hunt Sales (the sons of comedy legend Soupy Sales) seemed to come out of nowhere on the heels of the singer’s most commercially successful period. But Bowie certainly needed a reset, particularly after Never Let Me Down didn’t even enjoy the commercial success its immediate predecessors did. While the noise-rock promised by Gabrels’ involvement didn’t really come through, the band seemed to forecast much of ’90s alt and grunge with its sound. Their best song is “Amazing” from their debut album, with its hypnotic escalating melody. It could easily have been an alt-rock radio hit in 1995 or so, and it would’ve been better than most other alt songs on the radio at that time.

79. “John, I’m Only Dancing” (1973, single)

Arguably the most prominent example of a song Bowie kept tinkering with over a period of several years, “John, I’m Only Dancing” was originally released as a non-album single in 1972, having been recorded just after the release of the Ziggy Stardust album. Bowie, though, was dissatisfied with this version (which remains the one you’re most likely to hear), so he re-recorded it multiple times afterward, first in October of ’72 and then again during the Aladdin Sane sessions the following year. Specifically it’s that last version, often called the “Sax Version”, that I’m ranking at this position as it’s a tighter, punchier cut than the others. It was yet another song that was yanked off an album at the last minute, with “Lady Grinning Soul” taking its place. This version was issued as another non-album single and given the same serial number as the original release. A drastically different version was recorded during the Young Americans sessions in 1975 and was released as “John, I’m Only Dancing (Again)” in 1979. Some itches you just can’t scratch, I suppose.

78. “Neuköln“ (1977, “Heroes”)

One of the Bowie/Eno “Heroes” instrumentals, “Neuköln” takes its title from the Berlin district of almost the same name (Neukölln). Bowie didn’t actually live in this district during his time in the city, but perhaps chose the name as it was the part of town where Tangerine Dream founder Edgar Froese, a major influence on the Berlin Trilogy, was from. Also, while tracks like this are seemingly designed to resist clear interpretation, the piece has often been read as referring to the desperate situation of many of the Turkish immigrants who’d settled in the district. However you want to look at it, the track is gloomy and evocative, as most of the ambient pieces from this period are. The song is initially dominated by a classic Brian Eno soundscape, with Bowie’s wailing saxophone coming to the fore as the song progresses. Of all the German-influenced Bowie tracks from this time, this may be the German-est.

77. “1984” (1974, Diamond Dogs)

The Diamond Dogs LP is a lot of things, probably too many. While Bowie was shifting from Aladdin Sane to Halloween Jack, another glam-rock persona, he was also hoping to create a stage musical based off George Orwell’s seminal Nineteen Eighty-Four novel (and doing a lot of coke). Permission for the musical was denied by Orwell’s widow, so Bowie combined some of the material he’d prepared for it with the apocalyptic glam rock that largely populates Diamond Dogs‘ A-side. This particular track had actually been initially conceived and recorded for Aladdin Sane, which shows how long the artist’s shift to a funkier sound was gestating before its full realization on Young Americans. The wah-wah-heavy guitar sound is obviously hugely indebted to Isaac Hayes’ seminal “Theme from Shaft“, and the track’s inclusion on Dogs is a classic example of an artist in transition.

76. “Look Back in Anger” (1979, Lodger)

A frenetic track from Lodger, “Look Back in Anger” is pushed along by excellent drum work from Dennis Davis, an undervalued powerhouse on the skins. While the Berlin Trilogy weren’t devoid of up-tempo pieces, this track stands out particularly for its high energy. (Obligatory note that Lodger wasn’t recorded in Berlin despite being considered part of the Berlin Trilogy.) The new wave music that Bowie had so heavily inspired was becoming more and more prominent commercially at this time, and Lodger can be taken as a reaction to that (as could the following year’s Scary Monsters). Lyrically concerning a visit from the Angel of Death, the song bristles with the kind of electricity, both musically and attitudinally, that presages where Bowie would go next with his sound.

75. “Planet of Dreams” (1997, Long Live Tibet)

Co-written by and co-credited to Bowie and Gail Ann Dorsey, “Planet of Dreams” is one of the singer’s most satisfying ’90s tracks. Recorded after the sessions for Earthling concluded, the song is a major departure from that album, with its atmospheric, synth-heavy vibe washing over the listener. The duo contributed the piece to the multi-artist Long Live Tibet charity compilation album, and it wound up being the only time the pair were co-credited on an official release even though Dorsey was one of Bowie’s most frequent side players during his final decades. Their voices pair well together, and the song hints at what a potential Bowie-produced Dorsey solo album might’ve sounded like had that project ever come to fruition.

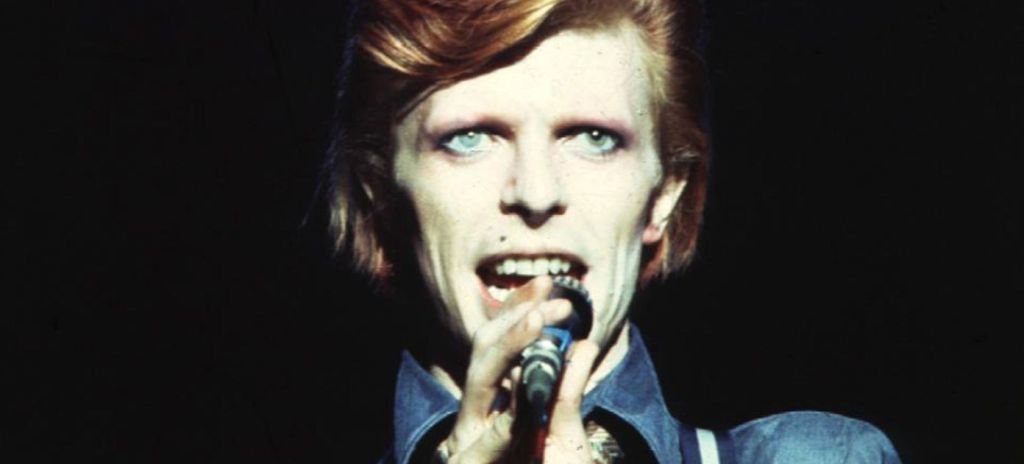

74. “The Jean Genie” (1972, Aladdin Sane)

The first song written for Aladdin Sane, “The Jean Genie” developed from a bus jam session between gigs on the Ziggy Stardust Tour. Bowie later finished the song in New York, claiming he wrote it for Cyrinda Foxe, a model who at that time was in Andy Warhol’s orbit. She would also appear in the promotional video for the song, and the track became the lead single for Bowie’s eagerly-anticipated Ziggy follow-up, hitting shelves in late ’72, over five months ahead of its parent album. The song is fairly straightforward, a stomping, Bo Diddley-inspired piece of rock n’ roll, with suggestive lyrics built around characters inspired by Foxe and Iggy Pop. Despite the obvious Yankee influences, the track became Bowie’s biggest hit single in the UK at the time, swaggering its way up to number two.

73. “Slow Burn” (2002, Heathen)

One of the best tracks from the 2002 Heathen album, “Slow Burn” features prominent guitar work from The Who’s Pete Townshend and is one of multiple songs from the album that were incorrectly assumed to be a reaction to 9/11. Bowie denied such a connection, claiming that everything for Heathen was written before that dark day, but did acknowledge a general feeling of unease he’d sensed while living in the US during this time. Like basically all of the original compositions on the record, the track is a mid-tempo alt-inspired piece, but it also carries the influence of his own ’70s works. The song also picked up a Grammy nod, an award Bowie received surprisingly few nominations for. (None of his ’70s work was ever nominated for a Grammy.)

72. “The Informer” (2013, The Next Day Extra)

My favorite track from the entire The Next Day project is this one, which was left off the album proper and instead included in the Extra EP which was released later in 2013. Lushly produced with a strong rhythm line and a memorable rising and falling synth part, the lyrics are inspired by writer/director Martin McDonagh’s excellent dark comedy In Bruges, but which also veer into “big questions” territory toward the end while maintaining a quasi-romantic sense at times. The “bum-bum-bum” backing vocals help, too. This is a real late-period gem, and one of the best sounding Bowie songs released on any project of his between Scary Monsters and Blackstar.

71. “Magic Dance” (1986, Labyrinth)

While the movie initially disappointed on release, it’s hard to argue that Jim Henson’s Labyrinth hasn’t gone to become one of the most iconic works in Bowie’s career. The kind of dark fantasy kids movie the ’80s specialized in, the film certainly is far from perfect, but it gave the singer, deep in his megastar phase, a chance to again slip into a different guise. The music from the film is, on the whole, not on par with Bowie’s strongest material, but like the picture itself, it’s aged much better than most of the other music he released during this period. “Magic Dance” still slaps as an ’80s dance number, with its playground rhyme-inspired opening lines and humorous goblin voices. The song is in many ways an update of Bowie’s “The Laughing Gnome” from 1967, but it’s the groovy hook that gets you in the door. Also I love the fact that the baby noises in the track were made by Bowie himself. That’s true dedication to the work.

70. “D.J.” (1979, Lodger)

Something resembling a straightforward pop song underneath layers of idiosyncratic production, “D.J.” can be read in many ways – as a criticism of DJs, as a sympathetic take on the disco era’s demands of DJs, as a take on Bowie himself (his birth initials are D.J.). However you wish to take it, the song is another sign of how Lodger Bowie is again evolving. The chugging rhythm and bizarro production value are in line with his earlier Berlin work, while the subject matter and undeniable hook feel like reactions to the changing music landscape and inform where Bowie would go next with Scary Monsters. The guitar solo from Adrian Belew is probably the most memorable choice Bowie and producer Tony Visconti made on the record, as they cobbled it together from multiple disparate takes to simulate the sound of someone scanning through different radio stations. An oddball, but inspired decision.

69. “No Plan” (2016, Lazarus (Original Cast Recording))

The title track to a posthumously-released EP, “No Plan”, like the other tracks on the release, was originally written for Bowie’s Off-Broadway Lazarus musical. (Bowie’s versions of the songs also appeared on the cast recording album the previous year). Like much of the similarly-themed Blackstar, which had also been released the previous year, this piece certainly feels like the sound of a man who knows he’s facing the end. There’s a haunting quality to Bowie’s voice, and the arrangement and instrumentation maintain the elegiac tone. In a theme that we’ll return to with regards to all his songs released during this era, I wish everyone could face death with such dignity.

68. “The Bewlay Brothers” (1971, Hunky Dory)

One of the most debated songs in the Bowie canon, “The Bewlay Brothers” is seemingly an odd choice to round out Hunky Dory. In an album full of whimsical pop songs, the closing and longest track is a spare, somewhat sinister-sounding stream-of-consciousness piece that finishes with a sort of bizarre, vocal-affected downward spiral. The lyrics feel more like the kind of free association one might imagine Bob Dylan or Van Morrison coming up with, and Bowie vacillated on their meaning at different points in his career. While many read a gay subtext into the words, the one topic that both the singer and his fans have mostly latched on to is his relationship with his older half-brother Terry, who was a major influence on the young David Jones in many ways, but who also struggled with mental health issues. Perhaps the only way to comment on a relationship that meaningful is with an intentionally obfuscatory song like this one.

67. “Rock ‘n’ Roll with Me” (1974, Diamond Dogs)

Co-written with his childhood friend and frequent backing vocalist Geoff McCormack/Warren Peace, “Rock ‘n’ Roll with Me” was conceived for an aborted Ziggy Stardust musical project that became part of the stew of influences on the Diamond Dogs LP. The song aims to address Ziggy’s, and by extension Bowie’s, relationship with his fans, which the singer himself considered complicated. Musically, Bowie and McCormack drew from the R&B music they’d listened to as children, and the song plays out as another foreshadowing of where the artist would take his sound on the forthcoming Young Americans. While the lyrics aren’t quite as straightforward as the music might make them seem, this is still a bright spot amidst the dystopian angst found throughout the rest of the record.

66. “Eight Line Poem” (1971, Hunky Dory)

One of the most plaintive songs of Bowie’s career, the low-key vibe of “Eight Line Poem” makes it easy to overlook amidst the pop pizzazz of Hunky Dory. Flowing out of the jaunty “Oh! You Pretty Things”, Bowie’s piano and Mick Ronson’s tasteful guitar noodling give just enough accompaniment to what is literally an eight-line poem set to music. The lyrics are fairly abstract, and attempts by critics and even Bowie himself to explain them don’t really bring much clarity. But by now, we should understand all too well that Bowie’s opacity was a feature, not a bug.

65. “Because You’re Young” (1980, Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps))

An underrated track on Scary Monsters, Bowie overtly dedicated “Because You’re Young” to his son, then known as Zowie, upon the album’s release. The singer had just been awarded custody of the boy after his long-brewing divorce from Angie Bowie when the track was recorded in April 1980. Musically, the song mixes verses built around an angular guitar riff with melodic choruses and a swirling outro to fine effect, with effective accompanying and backing vocals performed by whoever producer Tony Visconti could find around at the time. The Who’s Pete Townshend appears on the recording, performing some windmill chords while grumpily drinking wine in Visconti’s New York studio, though it can be hard to hear his contribution in the song’s mix.

64. “Sense of Doubt” (1977, “Heroes”)

Likely the most foreboding song Bowie ever put to record, “Sense of Doubt” feels like every German expressionist film you’ve ever seen run through a synthesizer and then slowed down. The dissonant sound came as a result of Bowie collaborator Brian Eno’s famed Oblique Strategies cards, with Eno and Bowie drawing cards that essentially gave each of them directly contradictory instructions. As dopey as that all sounds, the resulting track rivals “Neuköln” when it comes to pushing the ambient sounds of the Berlin Trilogy to their furthest extreme.

63. “Quicksand” (1971, Hunky Dory)

While not as musically spare or lyrically dense as “The Bewlay Brothers”, “Quicksand” provides a similar counterpoint to the largely poppy nature of the rest of Hunky Dory. Bowie works in lyrical references to pretty much all of his favorite topics while producer Ken Scott weaves a sonic tapestry full of acoustic guitars, twinkling piano, and a lush string arrangement. The singer later referred to the track as being an “epic of confusion” that was inspired by his recent foray to America, though most of the historical figures namechecked in the song are European. There’s a haunting beauty to it all, though, with Scott’s production really filling the track out and giving it life.

62. “V-2 Schneider” (1977, “Heroes”)

The most overtly Kraftwerk-style track from the Berlin Trilogy, “V-2 Schneider” is literally named after that band’s co-founder Florian Schneider, as well as (possibly) the V-2 rockets developed by German scientists during World War II and later used in the US space program. (Kraftwerk had referenced Bowie and Iggy Pop in the lyrics to “Trans-Europe Express”, itself a response to Bowie’s “Station to Station”). Almost an instrumental (the title is briefly sung, but those are the only lyrics), the song showcases how catchy material like this can still be, as the backbeat noodles its way into your ear and stays there, with Brian Eno’s soundscapes and an accidentally off-beat sax part from Bowie fleshing the piece out. This is one of those songs that could be two minutes long or two hours, and Bowie and his cohorts pack a lot into the song’s actual 3:10 runtime.

61. “Lazarus” (2015, Blackstar)

Released as a single in late 2015 ahead of the release of Bowie’s final album (and subsequent death), “Lazarus” unsurprisingly contains the same themes of mortality as most of the artist’s output during his final years. This one hits those beats about as bluntly as any of the tracks do, and a haunting, unsettling video from director Johan Renck only added to those vibes. Of course, the song also gives its title to the musical Bowie had worked on in his final years and serves as somewhat of a bridge between that project and the Blackstar album. As with the other Blackstar tracks, the piece is sonically dense and features some of the finest production of Bowie and his long-time collaborator Tony Visconti’s careers. Lyrically, Bowie forecast an increase in his fame after his impending death, with that prediction obviously coming true, noted particularly by the song becoming his first US top 40 single in almost 30 years within a week of his passing.

60. “Drive-In Saturday” (1973, Aladdin Sane)

Much of Bowie’s output during the early to mid-’70s is preoccupied with various dystopian futures, impending apocalypses, or future evolutions of humankind, with the overtness of these themes varying from track to track. “Drive-In Saturday” takes a page out of the “Oh! You Pretty Things” book and uses a chipper, ’50s doo-wop-style arrangement to tell the story of a post-apocalyptic future where people have to watch old movies to remember how to have sex. Bowie initially offered the song to Mott the Hoople, who turned it down (just as they had done with “Suffragette City” the year before, instead opting to record “All the Young Dudes”). Bowie then recorded it himself, and it became the second single released off Aladdin Sane. This is just as well, because I can’t imagine any other band/artist making a song like this work.

59. “Fame” (1975, Young Americans)

A massive North American hit for Bowie, “Fame” became his first number-one single in the US or Canada. Strangely enough, the combo of him and Beatles legend John Lennon (who co-wrote the song with Bowie and guitarist Carlos Alomar and also played on it) didn’t push it to similar success in the UK, where it stalled at #17. (Very odd since Bowie was far more commercially successful in the UK than in the US pretty much across the board otherwise.) Decidedly funky, the singer again covers darker lyrics with upbeat lyrics, though his harsh take on his own celebrity helped establish an entire subgenre of entertainment dedicated to seductive and destructive sides of success. The song also makes memorable use of Lennon as a backing vocalist, having him provide the “Fame!” interjections throughout at various pitches, including the descending run towards the end.

58. “‘Tis a Pity She Was a Whore” (2016, Blackstar)

Another of many songs Bowie would record and then later re-record, “‘Tis a Pity She Was a Whore” first surfaced as the B-side to his 2014 single “Sue (Or in a Season of Crime)”. Both tracks would then be reworked for inclusion on 2016’s Blackstar, and both album versions are improvements. For the lyrics, Bowie dug back to the 17th-century play ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore for inspiration, and the Blackstar version marries the dark lyrics promised by the title to an upbeat, jazz-hip hop-fusion backbeat and avant garde saxophone work from Donny McCaslin. While much of Bowie’s work from this period is elegiac in nature, this track is strident and propulsive, yet still in line with Blackstar‘s other musical influences.

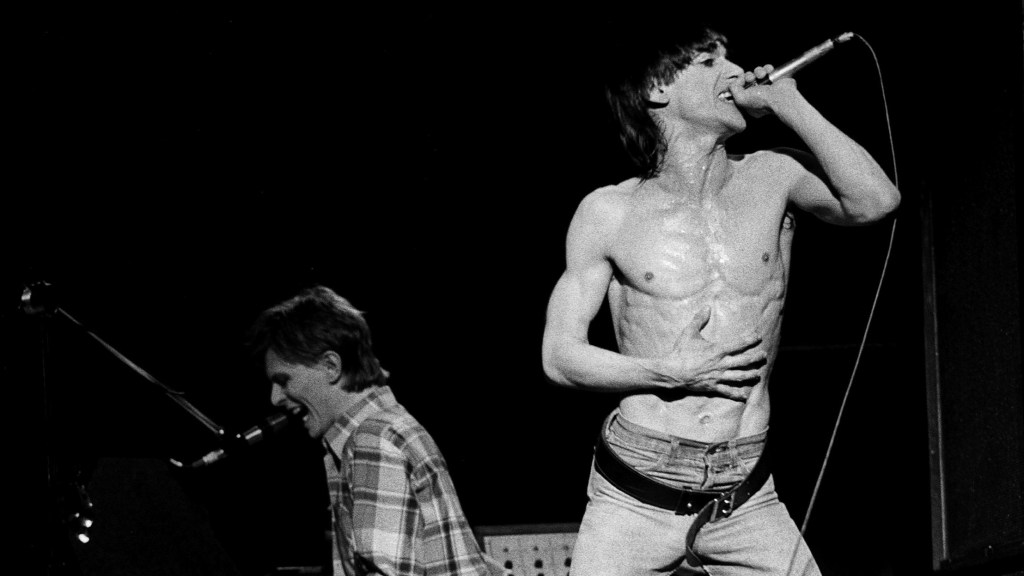

57. “Panic in Detroit” (1973, Aladdin Sane)

Bowie and Stooges frontman Iggy Pop became fast friends after meeting at a club in 1972, with the former agreeing to produce the landmark Stooges LP Raw Power. During their time together (and while Bowie’s career was ascendant in the wake of Ziggy Stardust), Pop became one of many Americans to exert an influence on what became Aladdin Sane, with “Panic in Detroit” emerging as Bowie’s take on Pop’s tales about being in the Motor City during the 1967 riots and the rise of the White Panther Party. A classic Bo Diddley beat became the backdrop for another quasi-apocalyptic track from this era of Bowie’s career, with Geoff McCormack adding some Latin percussion to give the singer the drum sound he wanted after Spiders drummer Mick Woodmansey refused. McCormack also contributed to the backing vocals, which are one of the track’s most memorable elements.

56. “Moss Garden” (1977, “Heroes”)

The second of the three consecutive ambient instrumentals on the “Heroes” B-side, “Moss Garden” is the least German-influenced. Rather it was Bowie’s previous visits to Kyoto, Japan that informed the track the most. On it, he plays a koto, a large stringed instrument very closely associated with Japanese music. And the title comes from an actual moss garden at a Buddhist temple in Kyoto which has become a popular tourist destination. Nestled in between the foreboding “Sense of Doubt” and the despairing “Neuköln”, this piece lightens the mood significantly and is one of Bowie’s most serene recordings.

55. “Fashion” (1980, Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps))

If Scary Monsters can be read as an artist taking stock of himself against a shifting cultural landscape, perhaps that theme is most clearly represented in “Fashion”. Bowie became as much a style icon as he had a successful musician in the early ’70s. and his discomfort with the rise of a new generation of successors/imitators is clear here (as it would also be on the same record’s “Teenage Wildlife”). He also memorably invoked fascist imagery to deride the fashionista types who demand anyone fashionable strictly adhere to current trends, with the singer also working in some contradictory lyrics as a way to perhaps address his own sometimes precarious fashionability. Many of the people who made fashion their whole personality took this song as an anthem, but that was certainly not how Bowie intended it.

54. “Breaking Glass” (1977, Low)

The second track on 1977’s seminal Low (and the first with lyrics), “Breaking Glass” is very brief, but memorable. In less than two minutes, listeners are treated to Bowie’s fractured lyrics, some memorable synth work from Brian Eno, and a very funky backbeat laid down by Bowie’s preferred rhythm section during this period, bassist George Murray and drummer Dennis Davis, who are also credited co-writers on the track. While much is rightly made of the ambient experimentation found on Low‘s B-side, the A-side material is very meaningful and influential in its own way. A longer live cut was released as a single in 1978 to promote Bowie’s Isolar II Tour, and it’s also strong.

53. “Fascination” (1975, Young Americans)

Based on a song a then-little known Luther Vandross had written titled “Funky Music (Is a Part of Me)”, “Fascination” is as overtly funky as Bowie got during his funk-adjacent Young Americans period. Vandross had been working as a back-up singer on the Diamond Dogs Tour in 1974, and “Funky Music” was a song the warm-up band would play before Bowie would take the stage. The reworked version, with new and typically opaque Bowie lyrics, would become Vandross’ first published songwriting credit when Young Americans was released the following year, which was a financial boon to the struggling singer. As with any good funk song, the calling card is the bassline, a real snarler laid down by session man Willie Weeks.

52. “Bring Me the Disco King” (2003, Reality)

A song first written and recorded for 1993’s Black Tie White Noise, Bowie and that album’s producer Nile Rodgers weren’t satisfied with it and decided to omit it from the record. Bowie tried again with a different version recorded for 1997’s very different sounding Earthling, but that, too, was considered not up to snuff. Bowie and producer Tony Visconti, with whom the singer had reconciled in the late ’90s, radically reworked the piece for 2003’s Reality. An album closer that sounds rather different from all the previous tracks, “Bring Me the Disco King” became a stripped-down piano-driven piece, with Bowie mainstay Mike Garson on the ivories and session drummer extraordinaire Matt Chamberlain pushing everything forward with a hypnotic beat. The odd thing is Chamberlain was actually playing a different song, but Visconti created loops of his performance and used them as the spine for this piece. The result is one of Bowie’s finest latter-period recordings.

51. “Dollar Days” (2016, Blackstar)

The beautifully arranged penultimate track on Blackstar, “Dollar Days” is one of multiple tracks on the record that reminds us of the importance of sax player Donny McCaslin and his jazz quartet to the record. Unlike the other songs on the album, “Dollar Days” was composed and arranged in the studio with no demo recording. McCaslin’s sax work shines on the piece, while Bowie’s lyrics address his mortality in much the same way the other Blackstar songs do. It would’ve made a great album closer, but Bowie and Tony Visconti had options to pick from for that spot. Instead the track stands as perhaps the most overlooked song from the record.

That’s it for part one. Numbers 50-1 will be revealed for part two.

Leave a comment