Numbers 100-51 are in part one here. And we press on.

50. “TVC 15” (1976, Station to Station)

One of Bowie’s most willfully bizarre tracks, “TVC 15” begins with a boogie-woogie piano intro, which is joined by a golden oldies-style vocal line from Bowie. While the vocals are buried in a surprisingly busy mix, the lyrics tell a tale about the narrator’s love interest being swallowed by a TV set, which apparently was taken from a dream Iggy Pop once had. Despite the proto-Videodrome imagery, the track mostly maintains a jolly, rollicking vibe, but there are elements in the mix that allude to the darkly surreal lyrical content, such as increasingly hard-edged guitars as the track progresses. It’s a hard piece to really pin down even all these years later, but its baffling nature is what makes it so alluring.

49. “Seven Years in Tibet” (1997, Earthling)

The best of Bowie’s various ’90s genre experiments, “Seven Years in Tibet” stands in contrast to the drum-and-bass tracks that populate the rest of Earthling. Here, the singer goes for a more industrial, droning alt sound, with a striptease-ready beat providing the backdrop for Pixies-style dynamics and a seductive sax line. The track was born out of a Reeves Gabrels instrumental originally titled “Brussels”, with Bowie reworking it after Gabrels convinced him to use the song. The lyrics were inspired by the novel Seven Years in Tibet, with Bowie having had the region on his mind at the time. (He’d also contributed “Planet of Dreams” to a Tibet benefit compilation record around that time.) But where many of his other ’90s efforts feel dated in a bad way, this one carries the unmistakable stamp of the decade while still sounding fresh.

48. “Boys Keep Swinging” (1979, Lodger)

The lead single from Lodger, “Boys Keep Swinging” divided critics upon release, as its parent album would. The track is a funky new wave piece with some unexpectedly complex rhythm work. Tony Visconti’s bassline during the build-up in the chorus is particularly memorable, as is Adrian Belew’s characteristically wonky guitar solo. That’s also guitarist Carlos Alomar on drums, as co-writer Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies card for this recording suggested the band members switch instruments. Lyrically, Bowie refers to themes of gender identity here about as bluntly as he ever did, with lines like “Other boys will check you out” and David Mallet’s drag-filled music video being the cause of some pearl-clutching in the UK. (The song wasn’t released as a single in the US because of RCA’s fear of how the gender-bending themes would go over.)

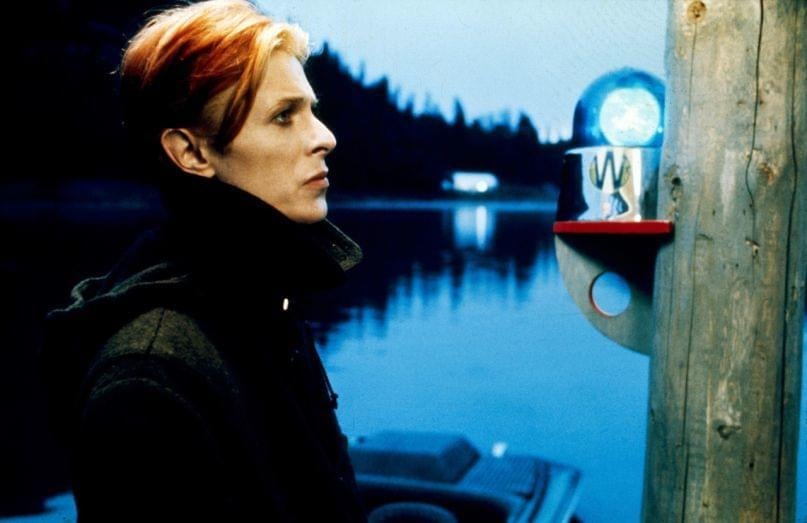

47. “Subterraneans” (1977, Low)

The final track on Low, “Subterraneans” was originally conceived and recorded for a potential soundtrack album for The Man Who Fell to Earth, with the initial tracks laid down in Los Angeles in late 1975 just after Station to Station was completed. Bowie revisited the piece while working on Low, and overdubs were added at both of that album’s recording locations – the Paris suburbs and West Berlin. Brian Eno reversed the guitar and bass contributions of Carlos Alomar and George Murray, while Bowie added some of the most expressive saxophone-playing of his career. Not a true instrumental, the song is still a tremendous mood piece, as emblematic of his Berlin Trilogy work as any of his tracks from this period.

46. “Loving the Alien” (1984, Tonight)

Along with the aforementioned “Blue Jean”, “Loving the Alien” is one of only two solo Bowie compositions to appear on 1984’s Tonight. Comparatively to the rest of the album and much of Bowie’s ’80s superstar phase, the track is a towering achievement. The song marries the contemporary pop sound of the era with an impassioned lead vocal and an ethereal atmosphere. The singer later stressed that the less slickly-produced demo version was far superior to the glossier album cut, but this is one case where the heavy production values of the time do bring something extra to the material. But the song’s expressive, religion-themed lyrics play well in multiple forms, such as the stripped-down live versions from Bowie’s final tours.

45. “It’s No Game (No. 2)” (1980, Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps))

Bowie had a habit of starting and ending his albums with similar motifs, either musically or through other means. 1980’s Scary Monsters album takes that concept the furthest by starting and ending the record with two different versions of the same song. As mentioned in part one, “It’s No Game (No. 2)” was a late replacement for “Crystal Japan” in the album-closer spot. It and the song it replaced were actually two of the earliest tracks recorded for the album, with the louder, proto-industrial “It’s No Game (No. 1)” developing from this earlier, more laid-back version. While elements of “No. 1” are stunning, I prefer this version, which carries a sort of world-weariness with it that stands in stark contrast to the screaming, aggressive tone of its counterpart, though for maximum impact, take both renditions together as two parts of one whole.

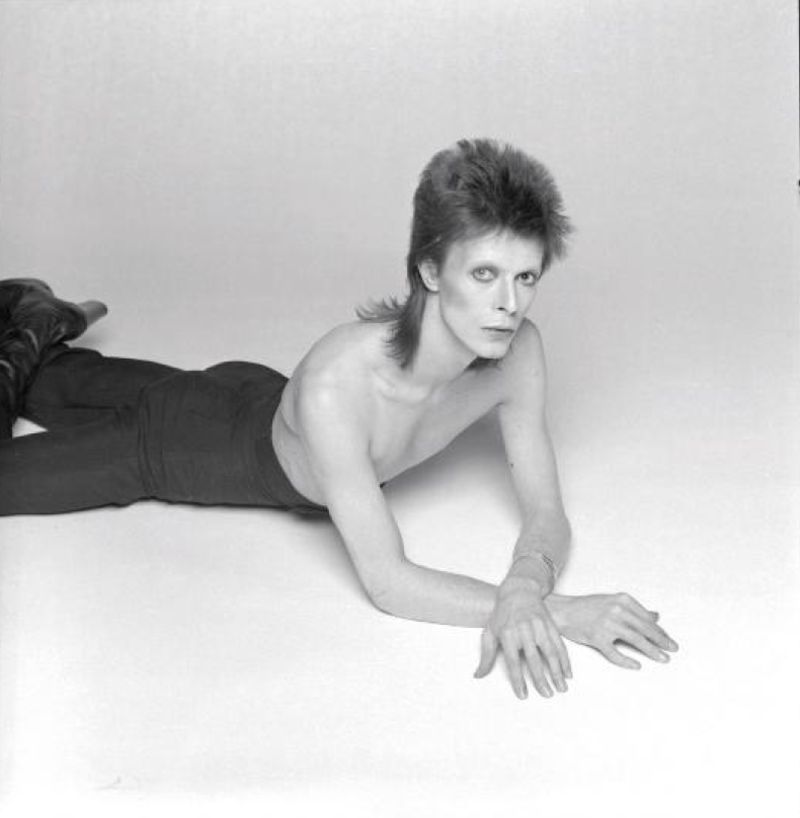

44. “All the Young Dudes” (1995, Rarestonebowie)

Famously written by Bowie and given to Mott the Hoople, of whom Bowie was a fan, “All the Young Dudes” became that band’s biggest hit and signature song. Here, though, we’re looking at Bowie’s version, recorded in late 1972 for Aladdin Sane, but left off the record and not officially released until 1995. While the two recordings are similar, Bowie’s version brings in a prominent saxophone line and lacks the preening vocal style that Ian Hunter employed on Mott’s version. But the track still retains its glam-anthem power, and it’s a wonder it took it so long to see any kind of official release.

43. “Stay” (1976, Station to Station)

Flat out, “Stay” is probably the funkiest Bowie song in his canon. With bassist George Murray and drummer Dennis Davis again laying down an incredible rhythm, guitarists Carlos Alomar and Earl Slick duel throughout the song to see whose six strings can snarl the most. According to Alomar (another of Bowie’s most frequent collaborators), the singer strummed out the chords for the song, and then Alomar, Murray, and Davis went to work on it, with Slick then coming in later and building further upon what Alomar had done guitar-wise. The result is a stunning piece instrumentally, showing exactly what the players Bowie had in his orbit during the mid-’70s could do.

42. “Cat People (Putting Out Fire)” (1982, Cat People)

There are two prominent cuts of this track, one credited to Bowie and Giorgio Moroder that appears in Paul Schrader’s weird 1982 horror remake Cat People and a solo Bowie version from 1983’s Let’s Dance. The original soundtrack version is far and away superior to the album cut, with its steamy, atmospheric intro and impassioned lead vocal performance. While it debuted in Cat People, I chose the still above to nod to the song’s finest hour, when it soundtracked Mélanie Laurent getting dressed and ready to take revenge on a bunch of Nazis in 2009’s Inglourious Basterds. That’s one of the best needle drops of Quentin Tarantino’s career, and it shone a spotlight once again on an overlooked Bowie recording.

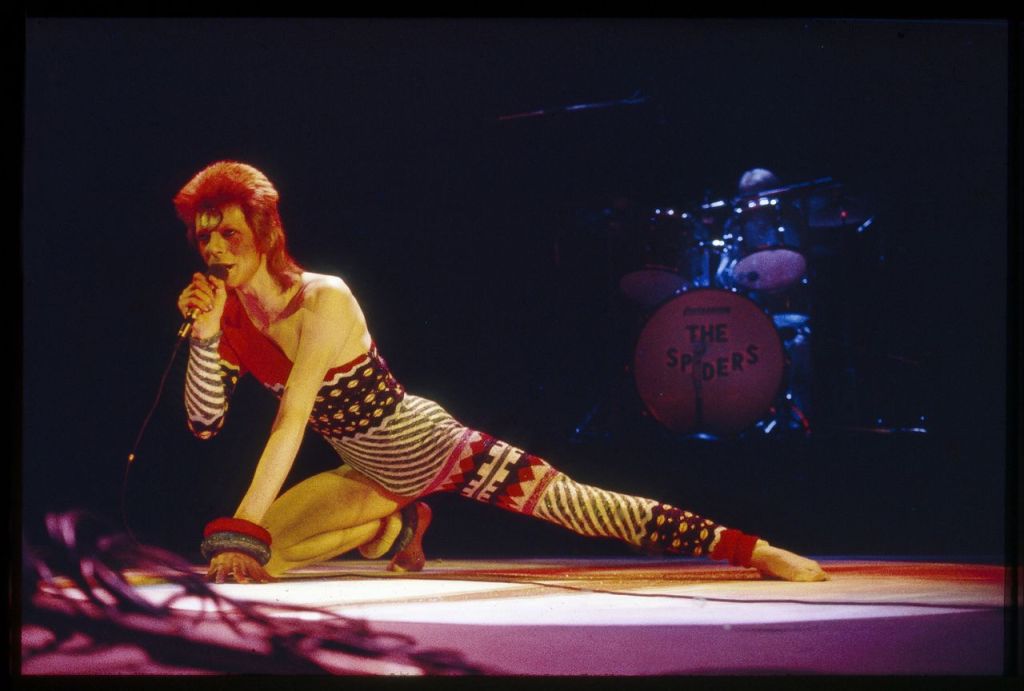

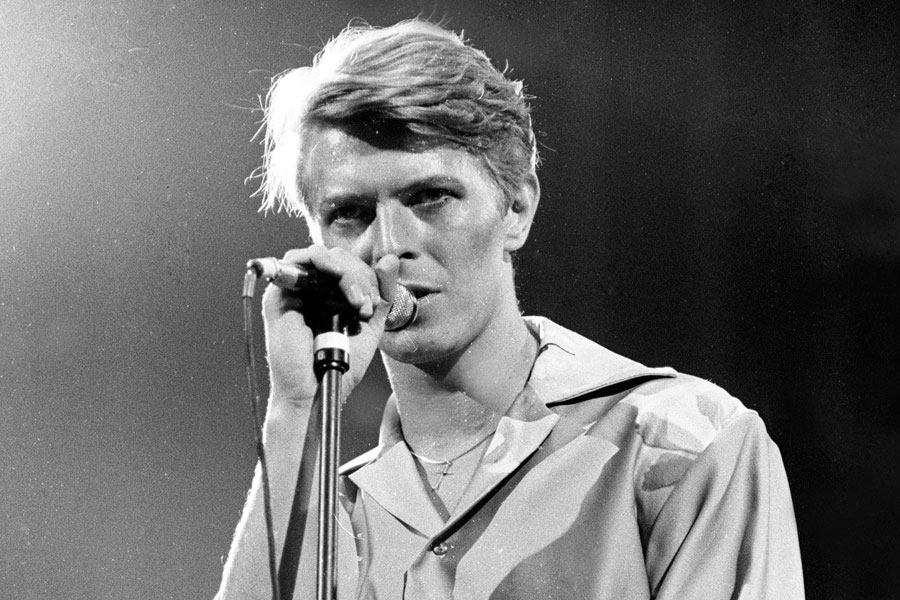

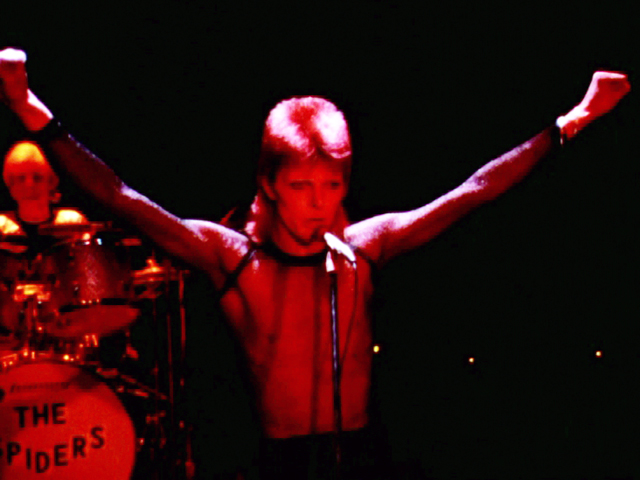

41. “Suffragette City” (1972, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars)

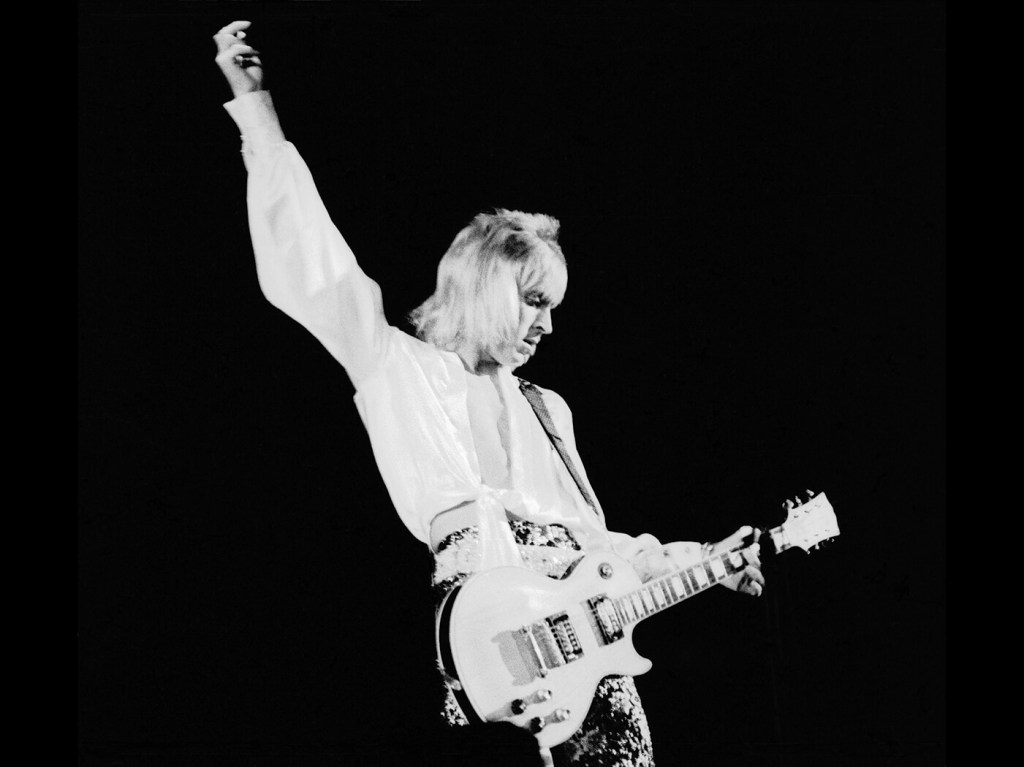

One of the most balls-out rockers of Bowie’s career, “Suffragette City” is a great showcase for the power of the Spiders from Mars. Mick Ronson’s roaring guitar drives things forward relentlessly, backed by sax-imitating synthesizers (a first for Bowie) and frenetic keyboards. The lyrics are all over the place, with references to old-time rock n’ roll, A Clockwork Orange, and Charles Mingus, while being more than a little sexual. But everything comes back to the relentless drive of the Spiders. Bowie could’ve been singing anything (and at times it feels like he was), and the part-Velvet Underground, part-Little Richard groove laid down by the band would’ve still carried the words along on a gale-force wind.

40. “Be My Wife” (1977, Low)

While a failure as a single, there’s a certain oddball catchiness to “Be My Wife”, the second single released from 1977’s Low. More of a straightforward rock song than pretty much anything on the album, the track still opens with ragtime piano played over noisy, wonky guitars. Then the main rhythm line kicks in, but even for a “straightforward” song, the beat is still very idiosyncratic, with Roy Young’s barrelhouse-style piano still prominent in the mix. The lyrics seem to be Bowie reflecting on the declining state of his marriage, but also dig into the general sense of loneliness he was feeling as he was trying to sober up after a lengthy period of heavy cocaine use.

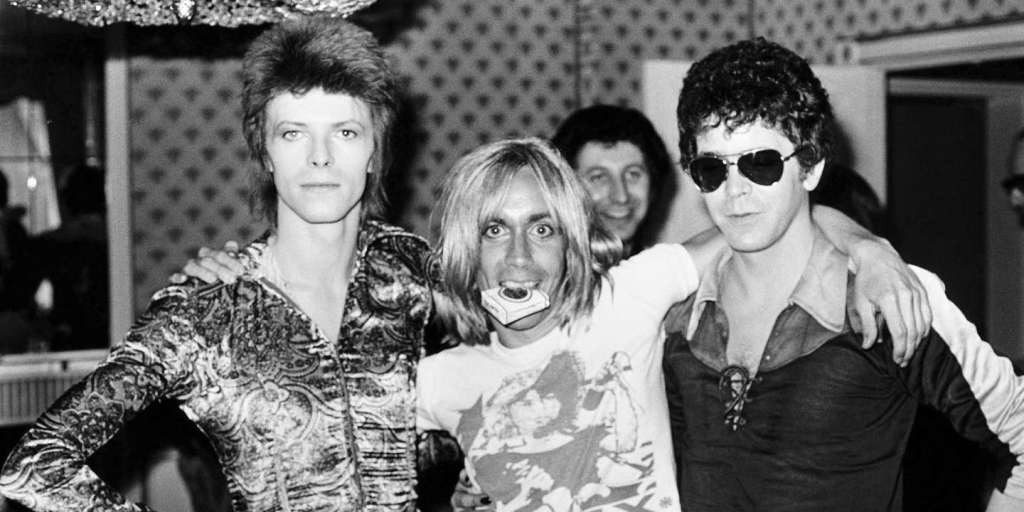

39. “China Girl” (1983, Let’s Dance)

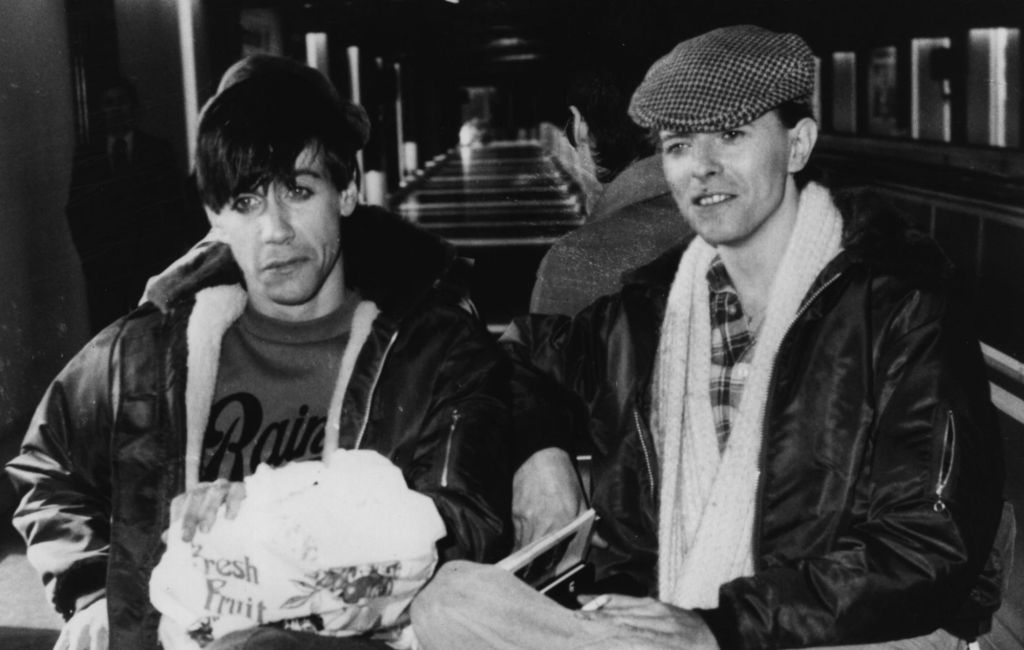

Probably the most prominent example of Bowie covering himself (in a way), “China Girl” was originally co-written by Bowie and Iggy Pop in 1976 for inclusion on Pop’s debut solo album The Idiot (which was released after a lengthy delay the following year). While not as rough and raw as many would’ve expected from Pop, this version of the song was still much rougher and rawer than the glossy pop version Bowie recorded for Let’s Dance in late 1982. Producer Nile Rodgers, assuming the song was a drug metaphor, decided to wrap the dark themes of the lyrics in as pretty an arrangement as possible, with the result being yet another huge hit single, going top-ten in the US and UK and becoming a major financial boon for the then-struggling Pop.

38. “Diamond Dogs” (1974, Diamond Dogs)

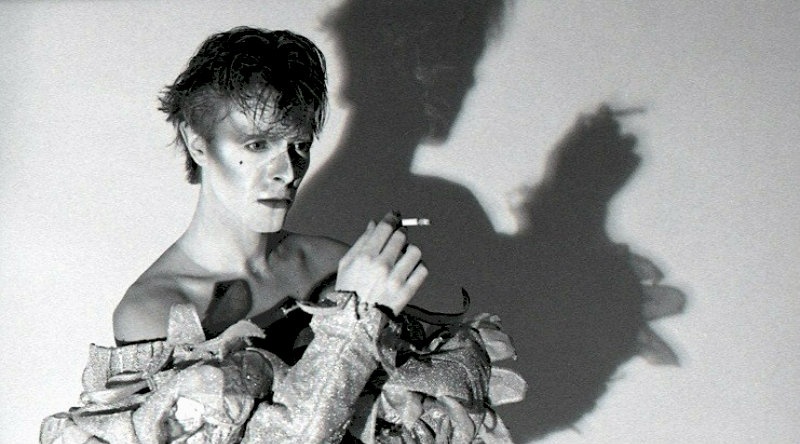

Title track and first proper song on Bowie’s bonkers 1974 LP (the spoken-word prelude “Future Legend” opens the album), “Diamond Dogs”, along with “Rebel Rebel”, sees the artist continuing the shape his glam rock sound by playing all the guitar parts himself and shifting more and more to a trashy, Rolling Stones-inspired vibe. While the rest of the album leans away from the glam influence, which Bowie would drop altogether afterwards, this track is still a raucous good time even as the lyrics paint an especially bleak picture of a dystopian landscape ruled by proto-punk gangs. Halloween Jack, a nominal new persona, was also introduced here, though the character never really developed any further. I remain curious what a more fully-formed version of the Diamond Dogs concept would’ve looked like, but as it stands, this track, like this album, serves as a capper to a fruitful era as Bowie pivoted to a new one.

37. “I Can’t Give Everything Away” (2016, Blackstar)

The final song from Bowie’s final album, “I Can’t Give Everything Away” is as fitting a swan song as one could hope for. Confronting his own mortality and mystique as directly as he would during this period, the track boasts a sly rhythm, with more great sax work from Donny McCaslin and a harmonica part that many have noted is reminiscent of 1977’s “A New Career in a New Town”. Jazz guitarist Ben Monder also contributes a fine solo towards the piece’s end. The track is a wonderful capper to the album as a whole, but pairs particularly well with its predecessor, “Dollar Days”. There’s certainly a melancholy beauty present throughout both tracks, with the singer also reflective about his own past in a way that provides a fitting coda to a career that leaves such a legacy.

36. “Rebel Rebel” (1974, Diamond Dogs)

Along with the title track, Bowie largely said goodbye to his glam rock days with “Rebel Rebel”, the lead single from Diamond Dogs. As the singer was moving away from the sound, the single nevertheless became a major hit for him and a glam-era anthem, particularly for women (a counterpart to how “All the Young Dudes” had become a glam anthem for men). While its place within the larger context of its parent album is a little fuzzy (the track was originally conceived for a Ziggy Stardust musical), the guitar sound achieved on the track is representative of what Bowie had hoped to achieve during this period. Session player Alan Parker claims it was he who actually played on this recording, and he certainly seems to have been in the studio at the time. But the credit for the guitarwork on all releases has always been given to Bowie himself. (Parker did receive a nod for his contribution to “1984”, the only guitar part on the album not credited to Bowie.) But however it came about, it’s incredible, and rock n’ roll can almost be defined by the string bend that bridges each chorus back to the main riff.

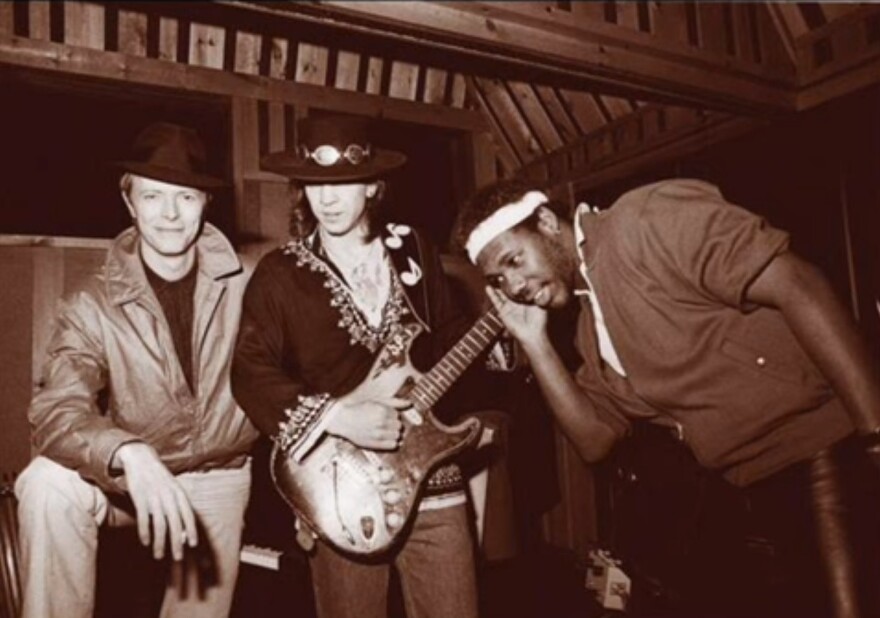

35. “Let’s Dance” (1983, Let’s Dance)

Like “China Girl”, “Let’s Dance” features some fairly ominous lyrics which are then placed into one of the catchiest pieces of music ever conceived. Producer Nile Rodgers, of Chic fame, worked extensively to create a pop arrangement for what was originally a folk-type song, and there’s no question he succeeded. Carmine Rojas’ bassline, working from a version that Rodgers and Erdal Kizilçay had come up with during the song’s demo phase, is memorably bouncy and infectious, and it becomes the backbone of an extended piece full of horns, impassioned vocals, and bluesy guitarwork from a soon-to-become-huge Stevie Ray Vaughan. While it’s easy to bag on Bowie’s superstar phase, there’s no denying the quality of the three main hits from Let’s Dance, and this song is a testament to Rodgers’ skills as a pop music maestro.

34. “Win” (1975, Young Americans)

One thing Bowie always seemed to understand was the importance of surrounding himself with talent. This was particularly critical whenever he decided to switch genres, and the Young Americans album is perhaps the clearest example of that. “Win”, like most of the album, is a fine showcase for the backing vocal trio of Ava Cherry, Robin Clark, and Luther Vandross. Clark’s husband, Carlos Alomar, was also a huge asset to the record and would work with Bowie extensively going forward, but so much of Young Americans is defined by those backing vocalists, who inject tremendous amounts of soul and at times almost a gospel feel to the record. Cherry was a love interest of Bowie’s during these years, and her presence seemed especially important. “Win” is one of the most successful tracks from this period for Bowie, showcasing what he can do with his own voice and the note-perfect contributions of these new collaborators he’d brought in to help get him musically where he wanted to go.

33. “Golden Years” (1975, Station to Station)

Possibly written for Elvis (the two legends’ reps had contact with each other around this time and the King sent Bowie a note before the latter went on tour), “Golden Years” continues the soul stylings of Young Americans, but changes up the feel. Many of the same musicians returned from the previous album, with powerhouse bassist George Murray joining the fray, but the backing vocalists didn’t return, with Bowie and his friend Geoff McCormack handling the singing on the track. And already the artist was mutating his sound, with the song bringing in a doo-wop feel and also incorporating a danceable, proto-disco vibe. The lyrics and vocals also generally have a bit more of an edge to them, perhaps presaging the rest of what would become the Station to Station record, which would incorporate wildly disparate musical styles into one of the artist’s most celebrated albums (even if Bowie himself claimed not to remember anything about the making of it due to his drug problems).

32. “Young Americans” (1975, Young Americans)

The title track to his 1975 LP, “Young Americans” was certainly a major departure for Bowie, his first non-glam single to be released in several years. While it underperformed in his native UK, perhaps unsurprisingly it was a bit of a breakthrough for him in the US, becoming his first top 30 hit here (and setting the stage for the huge success of the subsequent “Fame” single). The track also opened the record and introduced listeners to his new sound, his new backing musicians, and his own new coke-addled voice. Joyful musically, with a seductive rhythm and a memorable backing vocal arrangement, the song is a lyrical pastiche of Americana both positive and negative (a young Bruce Springsteen was an influence). While the inclusion of any positivity at all makes it perhaps upbeat compared to the apocalyptic themes of many of his prior works, “Young Americans” is still very much a Bowie piece, seemingly straightforward but with still something hiding just out of reach.

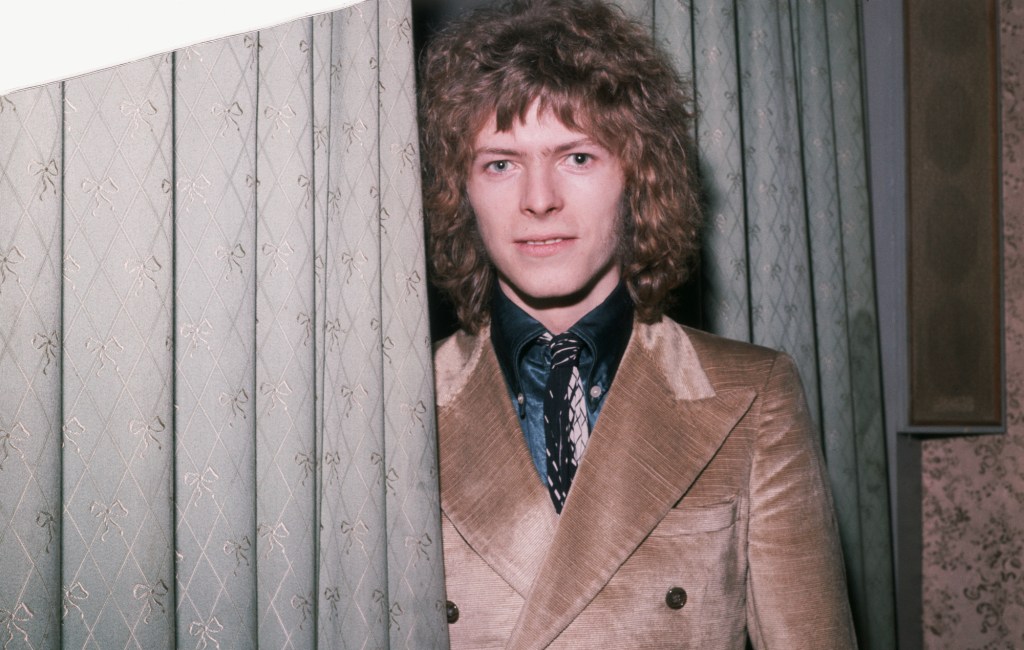

31. “The Man Who Sold the World” (1970, The Man Who Sold the World)

While maintaining the doomy feel of its parent album, “The Man Who Sold the World” stands out from the rest of the record in several ways. The recording is much more atmospheric, with the percussion mostly coming from a guiro for the majority of the piece and a spare arrangement built around Mick Ronson’s electric riff. The bass, played by producer Tony Visconti, is a secret weapon here, as it gives the song a propulsiveness that would normally come from the drums (which are low in the mix). The treatments on Bowie’s voice are especially effective, even if they were late additions to the piece due to the singer not writing the lyrics until the very last day of mixing for the album. The results seemed to surprise even Bowie and Visconti, who had grown frustrated with each other during the recording process and wouldn’t work together again for four years. Lyrically, the song is as cryptic as any of Bowie’s works, which is saying something, but there’s no denying the unsettling power of the words the man hurriedly cobbled together in a studio lobby one day in 1970.

30. “Who Can I Be Now?” (1991, Young Americans reissue)

Originally recorded for The Gouster, the first iteration of what would become Young Americans, “Who Can I Be Now?” was ultimately shelved, along with two other tracks, when Bowie’s sessions with John Lennon produced “Fame” and a cover of The Beatles’ “Across the Universe”. This was a shame, as this and “It’s Gonna Be Me”, one of the other omitted tracks, are stronger than many of the tunes that ended up on the finished album (particularly that “Across the Universe” cover, which is pretty rough). Lyrically on the nose enough that it later lent its title to the 2016 era-spanning box set covering Bowie’s coke-and-America period, the song is still uplifting in its way, with David Sanborn’s sax work and the faultless Young Americans-era backing vocals sounding almost cathartic.

29. “Speed of Life” (1977, Low)

The opening track from Low, “Speed of Life” immediately announces itself as something entirely different. An abrupt synth fade-in is followed by booming drums courtesy of Dennis Davis. While Brian Eno’s soundscapes are often the most celebrated aspect of the album, the drum sound Davis and producer Tony Visconti achieved here is among the all-time greats. The instrumental, a first for Bowie, then briskly rocks through its relatively brief running time, with a strong guitar/bass/drums groove augmented by the most extensive use of synths and keyboards yet heard on a Bowie track. The singer had planned to add lyrics, but finally gave up as he felt the piece was perfect as is. And he was right.

28. “Song for Bob Dylan” (1971, Hunky Dory)

Often dismissed as one of Hunky Dory‘s least essential tracks, “Song for Bob Dylan” boasts one of Bowie’s finest melodies and has a good-time feel to it even if that’s not really at all suggested by the lyrics. Invoking Dylan’s own homage to Woody Guthrie, “Song to Woody”, Bowie later remarked that he felt the song was about filling a leadership void in rock, calling it a track that laid out what he wanted to do in the genre. At the time, Dylan’s reputation had taken its first real hits with the release of the critically derided Self Portrait in 1970, so in that sense the song can be taken as homage to the icon of the ’60s and critique of him in the early ’70s (obviously Dylan would bounce back). Musically, it’s surprisingly catchy, with the “Here she comes” refrain in the chorus and the mix of Rick Wakeman’s piano and Mick Ronson’s guitar being representative of the strong pop arrangements present throughout Hunky Dory.

27. “Lady Stardust” (1972, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars)

As indicated in the “Ziggy Stardust” entry, Bowie’s most famous alter ego was an amalgam of several real people and some of Bowie himself (and then probably more abstract inspirations on top). One of the more prominent figures in this stew of influences was Bowie’s glam rock contemporary Marc Bolan, founder and beating heart of T. Rex. Bolan’s inspiration on “Lady Stardust” in particular is seemingly confirmed with the demo version of the song being titled “He Was Alright (A Song for Marc)”. The track itself has a very dramatic sensibility to it, based around Mick Ronson’s piano and featuring one of Bowie’s strongest vocal efforts. Lyrically, he paints a portrait of Ziggy as a romantic figure, adored by men and women alike – with the narrator confessing “a love I could not obey” for the title character – but with an unmistakable air of lament suggesting Ziggy’s ultimate fate.

26. “A New Career in a New Town” (1977, Low)

One of the brightest-sounding songs on Low, “A New Career in a New Town” brings to an end the record’s first side. Bookending the side with “Speed of Life”, the two instrumentals suggest the more expressive nature of the record while still sounding in line with the tracks that come in between them, all of which play more like traditional songs than the ambient, experimental flipside. Like “Speed of Life”, “A New Career in a New Town” was intended to have lyrics, but Bowie ultimately decided against including any. Instead we have a track that begins with synth before launching into a catchy, rock-style piece buttressed by some of Bowie’s most memorable harmonica playing. The title fittingly refers to Bowie’s then-upcoming move to Berlin (the track, like much of Low, was recorded outside of Paris). The song works as both a bridge between the album’s two disparate sides, but also as a cheery interlude in a record that can otherwise feel rather foreboding.

25. “Changes” (1971, Hunky Dory)

One of Bowie’s defining songs, “Changes”, like Hunky Dory, flopped upon release as a single only to become an enduring part of the artist’s legacy later on. Defined by one of Bowie’s strongest vocal efforts and Rick Wakeman’s piano work (shortly before he joined prog-rock group Yes), the piece sets the right tone for its parent album (it was the opening track) by laying out the jauntier pop feel the record would cultivate in stark contrast to the previous year’s harder-rocking The Man Who Sold the World. Notably, the track also includes Bowie’s first saxophone-playing on record, with that instrument being frequently employed by the singer going forward. Lyrically, it deals with Bowie’s already frequent musical reinventions, but also overtly discusses the importance of parents and wider society allowing teenagers to be themselves as youths. This was another of Bowie’s recurring themes from this era, and it would age along with the singer over the course of his career, as he would comment on generation gaps and youth from different perspectives as he aged.

24. “Fantastic Voyage” (1979, Lodger)

The default move for most albums, particularly ’70s albums, is to kick things off with something energetic, the kind of song you might also use as a live opener. Bowie, however, deviated from that practice multiple times in his career, with “Changes” opening Hunky Dory and the slowly building “Five Years” opening Ziggy just to name two examples. Another less-heralded occurrence of this is “Fantastic Voyage”, the serene and excellent opening number on Lodger. While establishing the theme of travel that runs through the LP’s first side, the track also deals with Cold War-era tensions and perhaps Bowie’s own mental state during the late ’70s. Brian Eno co-wrote the track, but is musically credited only with “ambient drone” while the piece is highlighted by three triple-tracked mandolin parts (two of them provided by producer Tony Visconti and guitarist Adrian Belew). Altogether, the track provides a very stately beginning to one of the artist’s often-undervalued records.

23. “It’s Gonna Be Me” (1991, Young Americans reissue)

A powerhouse soul number featuring some of Bowie’s finest vocal work, “It’s Gonna Be Me” was a painful omission from 1975’s Young Americans. Recorded in Philadelphia in 1974 (in between legs of the Diamond Dogs Tour, with the tour taking on a major soul influence afterward), the song was one of three tracks initially slated for release on what was then called The Gouster (along with “Who Can I Be Now?” and “John, I’m Only Dancing (Again)”) that were excised when sessions in New York with John Lennon yielded “Fame” and “Across the Universe”. More spare in its production value than most of the other tracks from this era, Bowie and his backing vocals trio of Cherry, Clark, and Vandross are all in spine-tingling form, and while the song arguably runs aground during its final sequence, there’s no denying what was achieved here. Hugely lamentable that Bowie’s most fully realized take on the soul genre was left off his soul album.

22. “Warszawa” (1977, Low)

The most striking of the ambient instrumentals that populate the Low and “Heroes” records, “Warszawa” was designed to recreate Bowie’s visit to Warsaw (Warszawa in Polish) in 1976. As the singer had to leave the studio outside Paris briefly to attend to a legal matter, Brian Eno constructed much of the track’s soundscape (and is listed as the only instrumentalist to perform on the piece), following Bowie’s directive to create something slow and emotive. When Bowie returned, he added the track’s brief vocal part, which is derived from a Polish folk melody, but is not actually sung in Polish. This was the final work done in the French studio where most of the album was recorded before the musicians departed for Berlin. Of the many collaborations between Bowie and Eno, this is the most fully realized.

21. “Ashes to Ashes” (1980, Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps))

The lead single from Scary Monsters, “Ashes to Ashes” marked a major commercial resurgence for the artist. His second number-one hit in the UK, the release also hit the top ten in multiple other European markets. While not a success in the US, the song and its landmark music video have gone on to become major parts of Bowie’s legacy, with the lyrics both resurrecting Major Tom from “Space Oddity” and seeming to confront the singer’s turbulent but successful ride through the ’70s. Musically, there’s a lot here. The beat is the first thing you notice, which is constructed to almost fool the listener as to the track’s time signature, with the vocal phrasing also following this pattern. Production and composition-wise, it’s one of the most satisfying Bowie singles, and the music video, co-directed by Bowie and David Mallet, only bolstered the song’s complex legacy further with its iconic imagery.

20. “Ziggy Stardust” (1972, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars

One of those perfect classic rock songs, “Ziggy Stardust” is built around an absolutely monster guitar riff provided by Mick Ronson, which became the perfect vessel for Bowie to spin a yarn about his alter ego, charting the extraterrestrial rocker’s rise and fall in a very direct way after the character had been more obliquely referenced on multiple prior songs on the LP. Aside from the main guitar hook, take further note of the work Ronson does through the verses as well, which adds extra flavor to Bowie’s vocals. On the vocals, Bowie’s in fine form here, synthesizing the various influences that went into the character he was portraying and coming out with a confident, strutting singing performance that places him in the same pantheon as some of the frontmen who’d inspired the performance (and far outstripping the work of others).

19. “Blackstar” (2015, Blackstar)

The centerpiece of and title track to Bowie’s incredible final LP, “Blackstar” suitably feels like something from another world. As the lead single and opening track on the record, it immediately lets listeners know that they’re in for something very different than The Next Day (or any previous Bowie record, really). Starting as an otherworldly electronic jazz piece (those adjectives only kind of describe it), the nearly ten-minute track shifts to a slower, elegiac, R&B-rooted middle section before returning to the original vibe towards the end. Seven-plus years on, the track still feels like something that fell out of the sky, defying categorization or easy analysis. Considering what it represented, the piece couldn’t have been more fitting.

18. “Sweet Thing” (1974, Diamond Dogs)

The centerpiece of the Diamond Dogs album, “Sweet Thing” as a standalone number can’t really be judged without including the following “Candidate” and “Sweet Thing (Reprise)” tracks. The suite features some tremendous vocal work from Bowie, with lyrics that bridge the different dystopian themes present on the record as a whole. (It began life as part of the proposed Nineteen Eighty-Four stage musical, but appears on the record’s less overtly Orwellian first side.) Bowie’s voice modulates from a low near-growl at the beginning into a full-on croon, showcasing the man’s range, with backing vocals during the chorus that sound superficially pretty but have an odd warble to them that telegraphs the dark nature of the words being sung. The song shifts sharply into the similar, but more discordant “Candidate” before returning for a dramatic, romantic-in-spite-of-itself reprise. Taken together, it’s a stunning piece, soaring yet also alienating.

17. “Starman” (1972, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars)

A seminal track in Bowie’s discography, which featured in an equally seminal TV performance, “Starman” in many ways established the David Bowie we would come to know and love. While “Space Oddity” had been a hit three years before, it was too easily (and unfairly) dismissed as a conveniently-timed novelty piece. Then the singer spent the next two years in the commercial weeds, struggling to catch his next break. “Starman” became that break, with its signature octave leap in the chorus and its spacey, hopeful lyrics (much more hopeful than most of Bowie’s other output around this time). All the Ziggy-era elements are here – the showmanship, a stew of pop influences, memorable guitar and arrangement work from Mick Ronson, and the sort of ethereality that was always tied in with Ziggy as a persona. Throw in a career-redefining live spot on the BBC’s Top of the Pops in the summer of ’72, and Bowie was now officially a thing. And the children boogied.

16. “Oh! You Pretty Things” (1971, Hunky Dory)

Perhaps the representative track on Hunky Dory, “Oh! You Pretty Things” is the perfect marriage of the album’s upbeat pop musical stylings and the rather nihilistic lyrics Bowie often traded in at the time. Making overt references to Friedrich Nietzsche, Aleister Crowley, and heavy sci-fi works like Arthur C. Clarke’s seminal Childhood’s End and Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s The Coming Race, the track was originally given to former Herman’s Hermits frontman Peter Noone, who released it as his debut solo single in 1971, with the song reaching #12 in the British charts. Bowie reworked the song for his own version, with a dynamic arrangement that juxtaposes the music hall-esque piano-led verses with more bombastic choruses that feature the future Spiders from Mars. The burgeoning apocalypse has never sounded so good.

15. “Modern Love” (1983, Let’s Dance)

The best of Bowie’s pop superstar songs, “Modern Love” again reframes uncertain lyrics (which repeatedly question faith in both people and higher powers) within the context of an upbeat pop song. As opposed to “Let’s Dance” and “China Girl”, the other two big hits on the record and also the next two tracks on the LP, “Modern Love” has the energy of a rock song, with the funky opening guitar riff setting the stage for an up-tempo piece that barrels right through all of Bowie’s grand lyrical questions. The interplay between the lead and backing vocals is also a highlight as it underpins the majority of the song. A great album opener, this is the kind of song that can instantly inject energy into almost any room.

14. “Always Crashing in the Same Car” (1977, Low)

A harrowing track from Low, “Always Crashing in the Same Car” derives its title and lyrics from one particular low point during Bowie’s drug years (he repeatedly rammed the car of a drug dealer he believed had ripped him off and then drove his damaged vehicle in circles around a hotel garage afterward) as a metaphor for a cycle of mistakes and failures. The track is incredibly atmospheric, with Bowie’s eerily calm vocals being placed above the music via Brian Eno’s treatments, and then a deeply underrated guitar solo from session man Ricky Gardiner spiraling through the song’s latter stages. Given the personal problems Bowie was trying to overcome during this stage, there’s an added momentousness to this piece.

13. “Time” (1973, Aladdin Sane)

Another of Aladdin Sane‘s tracks that makes excellent use of pianist Mike Garson, “Time” sees Bowie and his Spiders work in cabaret mode, with Garson’s piano work inviting comparisons to burlesque music and the work of European composers like Jacques Brel or the pairing of Brecht and Weill. (Bowie would cover material by these men at different points in his career.) Mick Ronson doubles many of Garson’s parts on guitar, and the song becomes bombastic and swirling as a result, cinematic in scope. Bowie’s lyrics famously invoke terms like wanking, quaaludes, and red wine, but deal with big themes, particularly mortality (New York Dolls drummer Billy Murcia had recently died and is namechecked in the track). The lyrics as a whole tend to divide critics, but to me they feel right in line with where Bowie was at this time and where he was going.

12. “Watch That Man” (1973, Aladdin Sane)

The kind of sloppy, sleazy, kick-ass rock song that The Rolling Stones made an endless career out of playing, “Watch That Man” kicks off 1973’s Aladdin Sane by foreshadowing the influence the British quintet would have on Bowie’s glam sound in the coming year-plus. With a mix from Bowie and co-producer Ken Scott that buries the singer’s vocal down among the raucous instrumentation, the track is yet another Aladdin Sane number that divides opinion. But as a vibe piece, it’s one of Bowie’s strongest. The Spiders (with pianist Mike Garson and sax man Ken Fordham in tow) have as good a time here as they’d do with any track, and Bowie and his backing vocalists successfully convey the decadent rock-star attitude of the song just as well as any other rock frontman of the era could’ve done. Bowie the butt-kicking rock god is a mode of his that isn’t appreciated enough.

11. “Queen Bitch” (1971, Hunky Dory)

The most guitar-centric track on the otherwise piano-driven Hunky Dory, “Queen Bitch” is one of three songs on the record that were fairly overtly written about Bowie’s major American influences (“Andy Warhol” and “Song for Bob Dylan” are the others). The influence here is The Velvet Underground, whose final meaningful album, Loaded, had been released the year before (and obviously Bowie would work with Lou Reed on Transformer in 1972). The song might seem a bit too playful to be inspired by Reed and company, but the provocative lyrics and central guitar work clearly can be traced back to VU at different stages of their run. Aside from that outside influence, the track finds the future Spiders from Mars in top form, with Mick Ronson’s perfectly thrashy guitar tone and Trevor Bolder’s impressive bass work being standouts.

10. “Five Years” (1972, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars)

One of the rock’s great album-openers, “Five Years” kicks off the Ziggy Stardust album on an oddly subdued note initially, but the track’s increasing grandeur as it progresses fully establishes the cinematic nature of the rest of the record and of both Bowie and his iconic alter ego. (It also pairs well with album-closer “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide”). Lyrically dealing with an impending apocalypse that threatens to destroy Earth in five years’ time, the track is a masterpiece of production, with Bowie’s increasingly strained vocal matching the swirling intensity of the piece’s back half, with piano, strings, guitars, and more battling against each other in the mix, with Woody Woodmansey’s plaintive, perfect drum beat just stridently, inexorably bopping along, no matter how quiet or loud everything is around it.

9. “Sound and Vision” (1977, Low)

A joyous-sounding track from the largely chilly Low, “Sound and Vision” still manages to feature lyrics from Bowie that directly address his mental state at the beginning of his Berlin period (which actually started in France). While the words are fairly straightforward regarding the singer’s isolation, the groove is even more direct. The booming drum sound Dennis Davis and Tony Visconti achieved on the record is perhaps at its best here, with Davis slamming us into the track, joined by a funky bassline from George Murray and eventually some excellent, cascading synth flavor from Brian Eno. Backing vocals come in well before Bowie’s lead, with singer Mary Hopkin (Visconti’s wife at the time) having laid down her contribution before the decision to include lyrics was even made. Altogether, the track’s infectiousness and unique structure make it feel momentous despite its brief runtime, helping it become the biggest hit single of the Berlin years.

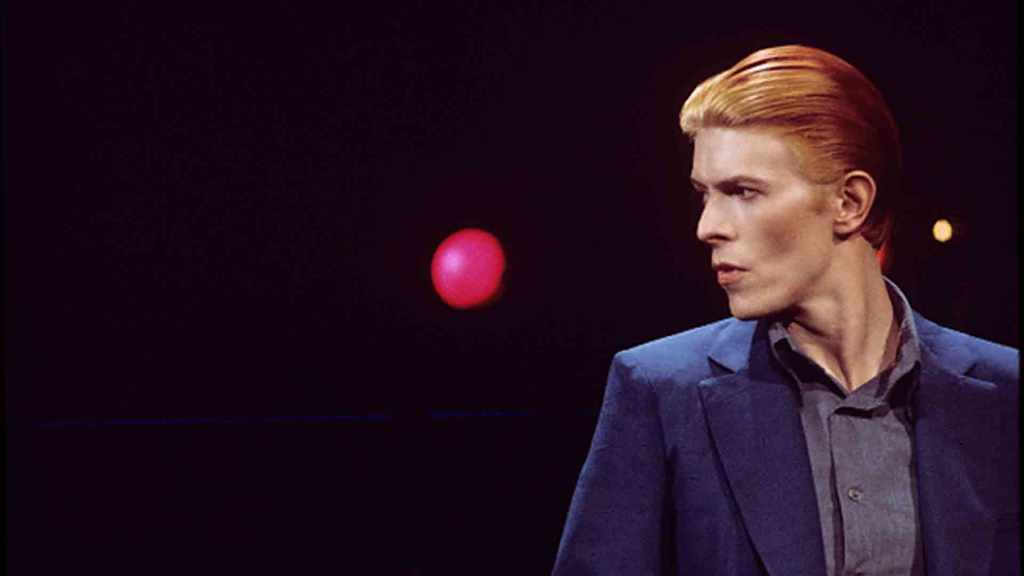

8. “Station to Station” (1976, Station to Station)

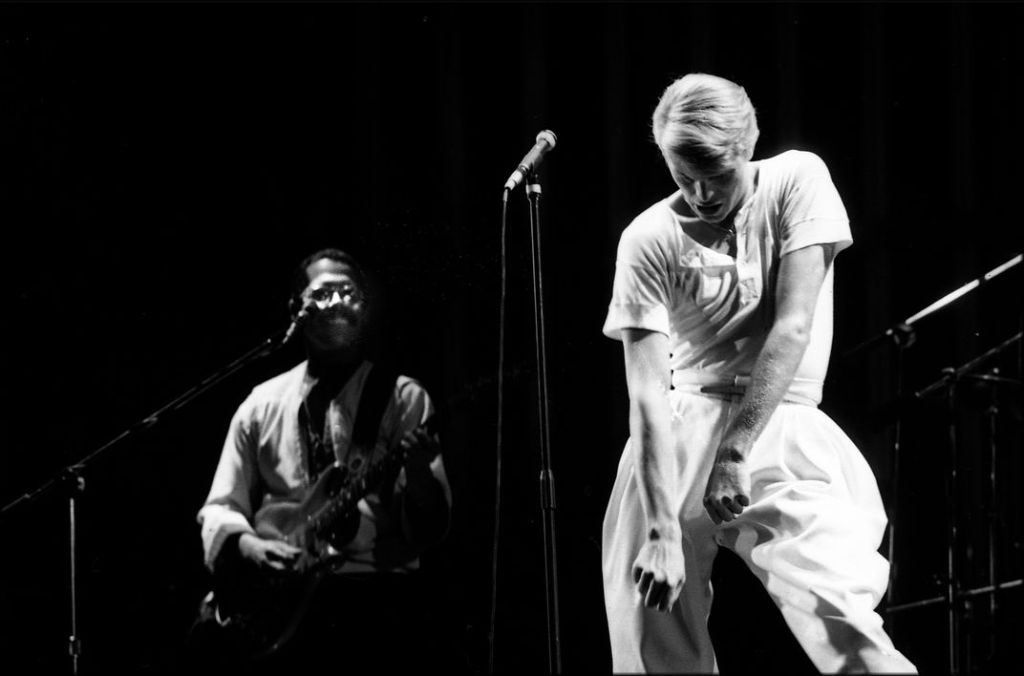

The longest studio track of Bowie’s career, “Station to Station” covers quite a bit of sonic territory. Opening with train-like sounds, the band comes in with a long, slow, thumping march, with notes drifting in and out of key before Bowie begins singing around three minutes in. The result is hypnotic and provides a perfect backdrop for the introduction of the singer’s most alarming alter ego, the Thin White Duke. About halfway through, the track abruptly switches to a completely different vibe, with Dennis Davis’ drums launching the band into the groovier second half, where Bowie reminds us repeatedly that “it’s not the side effects of the cocaine”. The dramatic “Wonderful, wonder who, wonder when” line in the first verse of the second half of the piece is one of the finest musical moments of the artist’s career, even if the song and its parent album are absolutely side effects of the cocaine.

7. “Space Oddity” (1969, David Bowie)

Bowie’s first hit in the UK and eventually in the US, “Space Oddity” was certainly perfectly timed. Hurriedly released as a single about three weeks after it was recorded, the song hit British shelves five days before Apollo 11 launched and nine days before one small step for man. The BBC used the track as background music for their coverage of the event, and the publicity helped the song hit number five in the UK. (It became Bowie’s first top-20 hit in the US when re-released here three years later and became his first number-one UK hit when re-released again in 1975). Tony Visconti, who produced the rest of Bowie’s sophomore album in the pair’s first collaboration, considered the song a novelty piece and passed production duties off to engineer Gus Dudgeon, who worked with the singer to craft a faultless recording. Every little sound effect, the vocal work, the atmosphere cultivated – all of it helps the track transcend mere novelty status (a status Bowie found hard to shake in the years immediately afterward) and push it to become undeniably his first major work.

6. “Life on Mars?” (1971, Hunky Dory)

In keeping with Hunky Dory‘s piano-driven, lyrically-surrealistic pop song themes, “Life on Mars?” could be considered a definite work. But more than that, its bombastic production showcases the cinematic aspects Bowie and his Ziggy-era cohorts would bring to the fore on the following record. Musically complex, the track begins plaintively with a single piano note, but grows significantly in intensity from there. Multi-tracked vocals, an enormous-sounding string arrangement from Mick Ronson, dancing piano work from Rick Wakeman, and even a recorder (also played by Ronson) figure into the track’s epic feel, along with Ronno’s brief but perfect guitar solos at the end of each chorus. All of this accompanies escapist lyrics full of mass media references, subverting the trope of small-town girls using the magic of film to transcend their dull realities.

5. “Teenage Wildlife” (1980, Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps))

While generally an upbeat-sounding track, “Teenage Wildlife” has always been taken as an unusually direct jab from Bowie towards many new wave-era artists whom he considered imitators. (Certainly Gary Numan, long considered the most likely subject of Bowie’s ire, felt that way about the track.) Working in this attack mode, the singer penned some of his most memorable lyrics, especially the verses that come after the first guitar break. And speaking of guitar, Robert Fripp returned to Bowie’s orbit after missing out on Lodger, and his playing sparkles all over Scary Monsters, especially here. The song is sneakily one of Bowie’s longest studio pieces, and lengthy guitar breaks from Fripp, with augments at various points in the track from Chuck Hammer’s guitar synthesizer, are a big reason why. The guitar work accompanies Bowie’s impassioned vocals perfectly throughout.

4. “Under Pressure” (1981, Hot Space)

Worked up in the studio from a Queen track originally named “Feel Like”, “Under Pressure” is a soaring collaboration with fairly humble beginnings. Bowie and the band were respectively working at Mountain Studios in Switzerland (Queen on their forthcoming Hot Space album and Bowie on “Cat People”) when they ran into each other and decided to work together. Initially Bowie contributed backing vocals to “Cool Cat”, which later appeared on Hot Space, but he didn’t like his performance and asked for it to be scrapped. Instead a bassline that’s been alternately credited to Bowie and Queen bassist John Deacon (Deacon credited Bowie, but everyone else says it was probably Deacon’s) led to scat singing, which led eventually to the final result, a definitive track for both artists and of its time. The contrasting of Bowie’s and Freddie Mercury’s voices never gets old, nor does the bombast the other Queen members bring to the proceedings.

3. “Moonage Daydream” (1972, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars)

Mick Ronson’s finest hour, “Moonage Daydream” is dominated by his mind-expanding guitar solo, but the track in its entirety is a major Bowie touchstone. As with “Watch That Man”, Bowie works in strutting rock star mode vocally while the track’s spacey lyrics and sound also make it a touchstone for the entire Ziggy Stardust era. The echo effects on the vocals in the track’s back half help prepare the listener for the guitar majesty that’s about to be unleashed, with Ronson finding one of the most satisfying guitar sounds ever put on record once he hits a barrage of string bends about 3:45 in. As a live number, the solo would continue to stand out as a stage highlight, but on record and combined with Bowie’s vocals and his own string arrangement, Ronson basically defines cosmic rock as a subgenre.

2. “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide” (1972, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars)

One of the greatest album-closers in music history, “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide” matches the slowly-developing bombast of its bookend track, “Five Years”. Beginning simply with strummed acoustic guitar, the track draws on numerous influences, from Jacques Brel to Charles Baudelaire to James Brown, with lyrics intended to bring the story of Ziggy Stardust to a suitably dramatic close. The arrangement for the piece escalates, as many Bowie tracks from this period do, slowly adding in more instruments and sonic layers before the singer’s cathartic “You’re not alone” line ushers in a new level of grandiosity, followed shortly afterward with an escalating run that feels like musical ecstasy. Altogether, these elements create something not seen before in rock music and which make just shy of three minutes feel like an entire lifetime.

1. “”Heroes”” (1977, “Heroes“)

The greatest song of all time, “‘Heroes’” is an exercise in sonic perfection. Soaring and triumphant during a time when the bulk of Bowie’s output was far from that, the singer felt the need to add quotation marks around both the song and its parent album’s titles just to add an ironic quality to the piece. An engrossing backing track – full of synth layers from Bowie and Brian Eno, a core groove provided by the rhythm section of Alomar/Murray/Davis, and Robert Fripp’s wailing feedback loops – was essentially completed before work even began on the lyrics. Those were added much later, with the singer improvising some of them at the mic. Famously recorded within sight of the Berlin Wall, the decisions to have Bowie change registers halfway through, the atmospheric Frippertronics, and the sudden appearance of backing vocals at 4:04 all land. Most songs struggle to have one perfect part, but there are multiple here, with the drum fill at 4:57 that leads the core band back into the main rhythm ahead of the “We can be heroes” refrain being one of those truly sublime moments in life, one we get to experience again and again.

Leave a comment