by William Moon

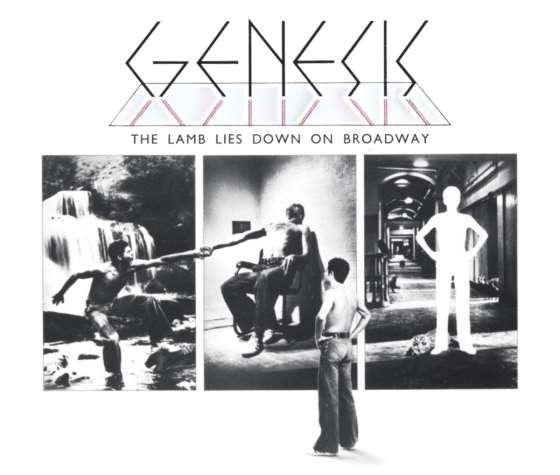

Starting a new feature here with The Bats**t Chronicles, wherein I dig into a project that succeeds or is memorable not in spite of being batshit crazy, but almost entirely because it is batshit crazy. (“Succeeds” is a malleable term here, as many projects in this vein are disasters by any traditional commercial metric, though our first subject does not fall into that category.) In an era where most blockbuster films are focus-tested within an inch of their lives and the mainstream music genres are dominated by algorithm-satisfying Franken-songs, it’s worth reaching back to earlier times, which while far from perfect, did allow for pure insanity to not only be created but in many cases become its own cottage industry. For this first entry in the Chronicles – think of it as Batshit Begins – we’ll take a look at Genesis’ baffling yet seminal 1974 double LP The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway.

I feel like these days awareness of Peter Gabriel breaks down in the following groups – those that don’t know who he is, those that know him just from his biggest hits, those that are fairly aware of his solo work and may passingly know he was once in Genesis, and those that are fully aware of his Genesis years and how different his public persona was back then. And when I say “different”, I mean it. Of course, the mere mention of Genesis is likely to cause a few to roll their eyes given the existence of songs like this, and the Gordian tangle of five-man Genesis, four-man Genesis, three-man Genesis, Gabriel’s solo work, Phil Collins’ solo work, and Mike + The Mechanics can be difficult to keep straight. But just know that old-school five-man Genesis, known for tracks like this, is worlds apart from the three-man Genesis that recorded this.

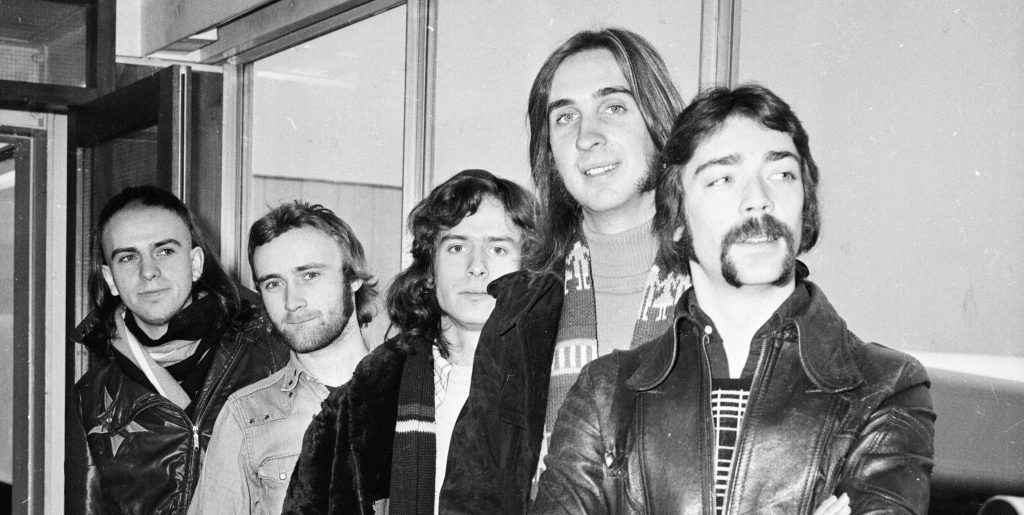

After a brief flirtation with ’60s folk and pop music on their odd debut album, the band began to drift into the English prog scene on their sophomore record, 1970’s Trespass, with “The Knife” in particular signaling a major shift in their sound. Original guitarist Anthony Phillips and a rotating cast of drummers were eventually replaced with Steve Hackett and Phil Collins in time for 1971’s Nursery Cryme, with album opener “The Musical Box” serving as a hell of an introduction to the band’s newest members. 1972’s Foxtrot was a commercial breakthrough, with Gabriel’s decision to wear a red dress and fox head on stage at a festival gig that year garnering press attention. From here, Gabriel would become arguably the most insanely costumed rock frontman in an era full of them.

Even greater commercial fortune came with 1973’s Selling England by the Pound, an aggressively British prog album that contains some of the band’s finest material and some stuff that’s part good/part ??? like “The Battle of Epping Forest”, an almost 12-minute piece that features Gabriel singing in various rather amusing voices about the misadventures of characters with names like Liquid Len and the Bethnal Green Butcher. But credit to the band for sticking to their unique guns, as the album became their first to hit the UK top five or chart at all in America (reaching #70). It also set the stage for a highly-anticipated follow-up, which early on in the planning stages the group decided would be their first double-album.

Like clockwork, the band had managed to crank out a new LP every year since their 1969 debut, with all but that first record being released in the autumn. Their label, now-defunct Charisma Records, would hold them to a fall release date again, but with a double-album in the works and a host of personal issues within the band cropping up, hitting that November 1974 target was exceedingly difficult. The sheer volume of material they’d recorded was a problem on its own, but added to that were issues with Gabriel briefly departing the project to work on a screenplay with The Exorcist director William Friedkin. After his return, his attention would be split again as his wife Jill began to have difficulties during pregnancy. (Bandmate Mike Rutherford has admitted that he and Tony Banks, who’d been in Genesis with Gabriel since their school days, were “horribly unsupportive” of the Gabriels during this time due to the pressure the band was under.)

All of that sounds like a lot, and it was a lot. But it’s not what makes the album batshit. What makes it batshit is the narrative concept. When the group were kicking around ideas for the record, Gabriel eventually pitched to the others what would become the story of The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway. Considering how bizarre the finished product is, talk that Gabriel’s original pitch was even more obscure is almost hard to believe. What could be more obscure than the final narrative, which plays out in songs with titles like “The Grand Parade of Lifeless Packaging” and “Here Comes the Supernatural Anaesthetist” and is so dense that Gabriel also included a full plot breakdown in the album’s liner notes?

As it is, we get the story of Rael, a Puerto Rican teenager in New York who goes on a bizarre journey through a series of strange, fantastical locations, most of which he reaches by simply being transported there through vague means. There’s sex with a series of snake women who all promptly die afterwards, a group of grotesque STD-ridden men who’ve already been infected by the snake women, then the castration of both Rael and his brother by a man named Doktor Dyper. As you do, both men carry their castrated penises in jars around their neck, but a raven steals Rael’s dick jar and flies off with it, as is a raven’s wont. (Quoth the raven, “Got yer dong!”)

This is all after Rael had a vision where his heart, covered in hair like hearts famously are, is removed and then shaved. The best part of this is that the song where this takes place is actually an instrumental written by Hackett and Banks, but it’s given the title “Hairless Heart” because we need to know that a furry heart was shaved during this piece. Oh, and this heart-shaving takes place in a dream during a flashback which began after Rael was swallowed by a giant cloud and then transported to a cave, from which he escapes into a factory, from which he also escapes into a hallway so he can have his flashback/dream/heart-shaving.

Gabriel, as he’d done on “The Battle of Epping Forest” and other tracks previously, sings in different voices at times to distinguish his characters, with Brian Eno being drafted in at the 11th hour to apply synthesized effects to some of the vocal parts to make things just that slight bit weirder. In a decade rife with over-the-top rock opera extravaganzas, Lamb is probably the furthest out there, at least narratively and lyrically. And like all of those records I just linked – except maybe Quadrophenia, which is the GOAT rock opera – Lamb‘s bloated run time is an issue. But dammit if it’s not still worth listening to.

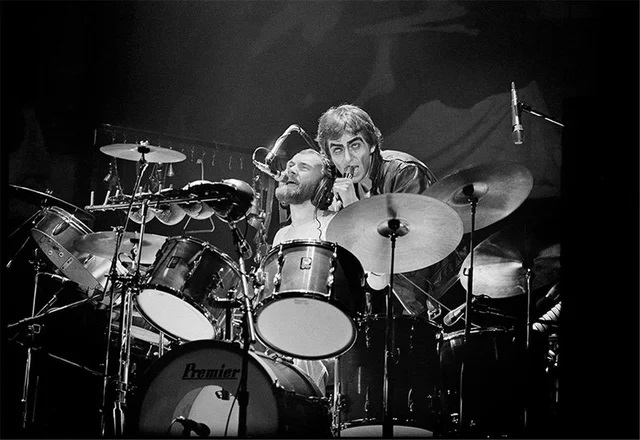

First off, this is still peak-era Genesis, a group composed of excellent musicians. Before Phil Collins became (however fairly or unfairly) a punchline, he was a hell of a drummer, and Tony Banks and Mike Rutherford were always the backbone of Genesis in whatever form. And guitarist Steve Hackett, often the forgotten member of the group, may arguably have been the most crucial to their sound during these years, as the band’s shift to a more poppy direction came after he left in 1976, not when Gabriel left the year prior. And everyone, Gabriel included, is in fine musical form here. “In the Cage” in particular just completely rips, with Banks firing off maybe the greatest keyboard solo in rock history. “Counting Out Time” is catchy and legitimately funny, with the main vocal hook being “Erogenous zones I love you!”. The title track, “The Carpet Crawlers”, “Anyway”, “Riding the Scree”, and “it“ are all standouts as well.

But beyond that, the whole thing is just bugfuck nuts. You can hear it in every track. One of the many influences Gabriel cited when coming up with the story is El Topo, the psychedelic 1970 western directed by Alejandro Jodorowsky, the godfather of batshit. And while it takes a lot of inspired lunacy to follow in Jodo’s footsteps, Gabriel and company give it a fair effort here. And whatever amount of hallucinogenic imagery is conjured up by the music on its own is further amplified when you consider the costumes Gabriel came up with for the ensuing tour, where the album was played in its entirety. The header image for this article features the singer in the Slipperman costume, equating to the STD-riddled characters mentioned above. The outfit is phallic in the most unsettling ways and exemplifies both the theatrical absurdity of the concert and the fraying relations between Gabriel and the other, non-costumed band members.

The ’70s being what they were, the album and tour were both very successful, at least on the surface. The record reached the British top ten, though it didn’t perform as well as its predecessor there. In the US, the album topped out at #41, far higher than any of the band’s other albums from this period. (Gabriel had intentionally used America as the setting and included numerous references to American figures and locations as a counter to the extreme Englishness of the band’s previous record.) The tour was well-attended and reviewed even as the band members felt somewhat stifled by the idea of having to play the full album each night, leaving room for only or two familiar tracks to be played as encores. And despite all the revenue generated at the gate, the band lost money due to the costly theatrics and arena deposits.

And while it can be fun to imagine a world where Gabriel continued with the band, there really was nowhere else for them to go together after this. Much as Pink Floyd’s later The Wall more or less ended that group as a functional unit, Lamb became the swan song for the five-man Genesis. Gabriel decided to leave the band early in the tour, with the final scheduled date being his last performance with the group as an official member. The band recorded two underappreciated records as a four-piece before Hackett left in 1976, reducing the lineup down to the trio that would become a major commercial success in the ’80s. Gabriel, of course, would soon embark on his solo career, with his debut single, 1977’s “Solsbury Hill”, being a metaphorical take on his departure from the band. That four of the five members of the band who made Lamb became absolutely massive pop stars in the ’80s (sorry Steve) is maybe the most batshit result imaginable.

And thus concludes the first chronicle. But there’s plenty more where that came from. Did you know Cat Stevens once recorded a concept album about math? Or that there’s a movie about a car tire that kills people by making their heads explode? (And that may not be the weirdest part.) So there’s plenty more stuff to dig into, and I’m interested in any suggestions. But, with Jodorowsky having been invoked here, the second chronicle is definitely going to be about Dune. So look for that coming soon.

Leave a comment