by William Moon

As promised, The Bats**t Chronicles returns with a sophomore outing covering Dune. (See the entry on Genesis’ The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway here.) And where to start with Dune exactly? Well, first off, this won’t focus on any one particular version of Dune and instead will look at the novel and how its various successful and unsuccessful adaptations have altered the perception of the overall franchise. And it should be noted that exactly how batshit you consider Dune to be is up to you, but it’s hard to argue that there’s not some batshit in there somewhere in its long and winding history.

Personally, I wouldn’t consider Frank Herbert’s original 1965 novel to be batshit. Grand? Yes. Wildly imaginative? Certainly. Massively influential? Definitely. Any crazier than a number of other expansive sci-fi or fantasy epics? Not really. While the concept of Dune – particularly if you view the spice in the story as an analogue for drugs – was pretty wild when it was first released, I’d argue that much of its content has been at least somewhat normalized in the years since then. Its own various and sundry film and TV adaptations are part of that, but also the way many of its trademark aspects have been echoed in subsequent works (such as Star Wars) have helped push it if not into the mainstream, at least much closer to it. The wilder parts of the saga began to set in with the increasingly “out there” sequel novels, and even more so when an all-timer of an avant-garde filmmaker put his indelible batshit stamp on the franchise in the mid-’70s.

The book was immediately successful, tying for the Hugo Award and winning the inaugural Nebula Award shortly after being released, and Herbert published the first sequel, Dune Messiah, throughout 1969. Hollywood took notice, with producer Arthur P. Jacobs first optioning the rights in 1971. His initial, more straightforward attempt to adapt the story to film abruptly came to an end when he passed away two years later. (He originally wanted the great David Lean to direct, and we can only imagine what that movie would’ve looked like.) This cleared the way for a group of investors led by Frenchmen Jean-Paul Gibon and Michel Seydoux to purchase the rights in 1974, and they tapped Alejandro Jodorowsky to direct. And here is where the batshittery really starts to take off.

First off, I could write forever about this particular attempt at filming Dune, and many other sites have already done so. And the 2013 documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune does a great job of laying out the relevant information, even if it never bothers to ask pressing questions about the ultimate feasibility of Jodo’s mammoth fever dream. (The movie was set to run between 10 and 14 hours.) I strongly suggest watching that doc if you haven’t. It may be more satisfying than any of the actual Dune adaptations that have graced big and small screens in the intervening years. Plus it gives you a chance to truly appreciate the visual splendor Jodorowsky and his team of dreamers cooked up.

And if nothing else, here is where the popular perception of Dune really shifted. Without websites such as this one or freely available Hollywood trades, it wasn’t easy for the “average fan” to follow the travails of Jodo and his merry men at this time, at least not like it would be now. But certainly Hollywood knew what was going on, and when everything eventually went bust, the dreaded word “unfilmable” began to get tossed around. It probably already had been lobbed about at least once going back to the Jacobs production, but it permeated any discussion about filming Dune going forward. When the project ultimately collapsed in 1976, Jodo’s backers sold the rights off to Italian mega-producer Dino De Laurentiis, which would pass through the hands of first Ridley Scott before winding up with David Lynch, whose 1984 version of the film bombed in theaters and has been largely disowned by the director himself. (The Jodorowsky project did resurface in 2022 in a sadly hilarious tale of crypto-bro hubris/misunderstanding of how ownership works.)

There’s much more to say about this stretch of Dune history and how long a shadow it’s cast over Hollywood, but the main thing I want to focus on is how much this 1974-1984 stretch still lingers over the franchise itself. The relative failure of Lynch’s project eventually opened the door for a TV miniseries adaptation in 2000, with another effort to put the story back in theaters finally culminating in Denis Villeneuve’s 2021 film, which has a sequel on the way. (Villeneuve and company took a cue from Ridley Scott, who first had the idea to split the novel across two films before he bailed to make Blade Runner instead.) Villeneuve (Arrival, Blade Runner 2049) is an excellent filmmaker, and his Dune was a success, at least by pandemic-era standards. It won the most Academy Awards of any film released in 2021 and made over $400 million globally. It’s visually stunning and well acted. The problems I have with it, though, are twofold – the decision to split the novel in half means the first movie just sort of ends in a random place, and compared to everything we’ve seen and heard about Dune films before, it comes off kind of dull.

Keeping up with the fever dream storyboards and design choices planned for Jodorowsky’s project would be largely impossible, and while Lynch has distanced himself from his own version, there are many suitably Lynchian absurdities in play there. (Also there’s music from Toto and these end credits, which…don’t feel very Lynchian at all.) But the casting is probably the easiest aspect of all this to examine. The current series makes smart, sensible casting decisions pretty much throughout. Jason Momoa as a dashing action hero, Oscar Isaac as a noble father and ruler, Josh Brolin as a grizzled mentor, Rebecca Ferguson as a tough-as-nails mother figure, Stellan Skarsgård as a truly hissable villain – all these and more are the kind of choices you make when you have a promising director, acclaimed material, and big studio money behind you. And that’s great, but then you inevitably compare this cast back to prior versions.

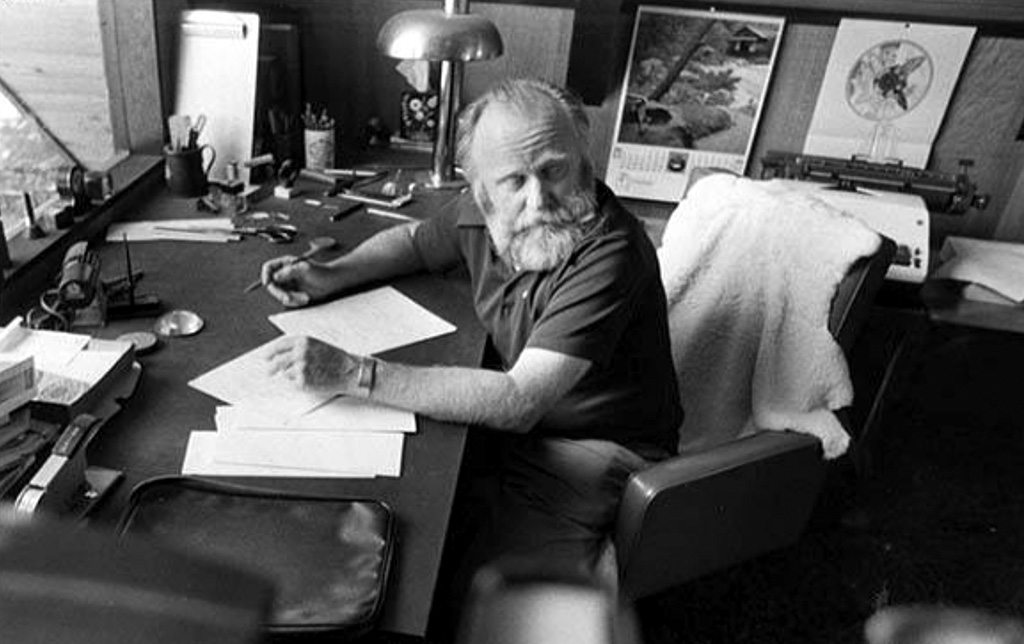

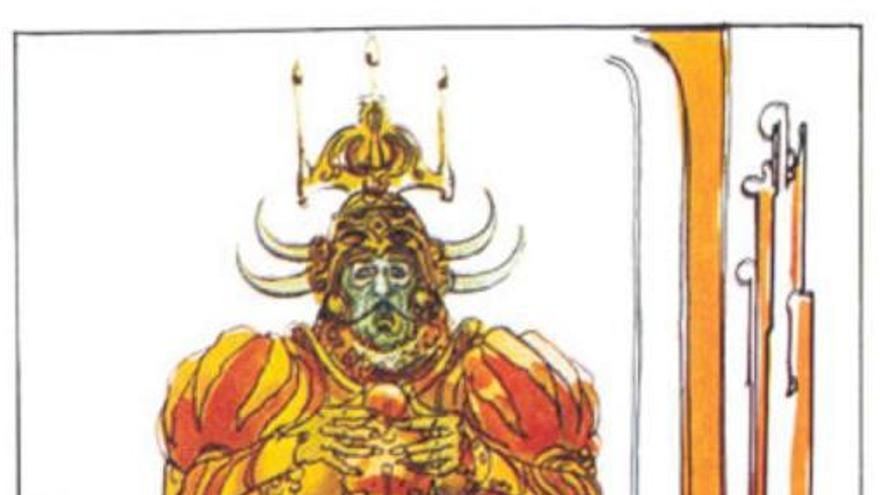

The role Brolin plays (Gurney Halleck) was filled by a pre-Star Trek Patrick Stewart in 1984, with…um…Hervé Villechaize tabbed for that role in Jodo’s version. (Villechaize missed out on the chance to wear blurry box armor and say, “Mood’s a thing for cattle and loveplay.”) Skarsgård’s villainous Baron Harkonnen was portrayed by a red-headed and ravenous Kenneth McMillan in 1984, with Orson fuckin’ Welles on the line for the role in the ’70s. (Production designer/visual artist H.R. Giger had developed much of the Harkonnen planet to look like Welles himself, with it all leaning into the horrific stylings of what would become his design for the titular villain in 1979’s Alien, a job he got thanks to his Dune connections.)

Jodorowsky’s most inspired/insane casting choice was likely Salvador Dalí as Emperor Shaddam IV, with the legendary artist demanding to be paid $100,000 per hour, with the filmmakers then planning to film his entire part in one hour and use a robot double (?!) to stand in for the Emperor in other scenes. For Lynch’s take, the role went to José Ferrer, in the discussion for greatest actor of all time. (He got to share scenes with this guy.) The character was omitted from the 2021 film entirely, but will be played by Christopher Walken in the upcoming sequel, which is an inspired choice in line with Dune casting traditions of yore. Another fitting one is Austin Butler, he of Elvis fame, as Feyd-Rautha, with the role having been played previously by one rock star, Sting, and promised to another, Mick Jagger, who would’ve apparently looked like this. (Florence Pugh will also join the cast in the sequel, playing Princess Irulan. I’d love for her to enter the film the same way Virginia Madsen did back in 1984, but alas…)

Another major elephant in the room obviously is the existence of Star Wars, with A New Hope in particular perhaps being uncharitably viewed as a broad simplification of Herbert’s sprawling narrative and a less committed realization of many of the designs and visions cooked up by the then-recently-deceased Jodo production. As we fast-forward from 1977 onwards, we travel through an era where George Lucas’ sci-fi/fantasy world became ubiquitous while Herbert’s remained somewhat of a white elephant, at least until a couple of years ago. And the version from 2021 that finally succeeded where others had failed did so solidly in Star Wars‘ wake, with the visual and narrative influence that once flowed in one direction now seeming to flow in the other. (For some lame reason, no one in the Star Wars camp found inspiration in Patrick Stewart carrying a pug into battle, nor did they make Emperor Palpatine’s throne look like a dolphin toilet.)

Villeneuve made a good movie, one that’s palatable for large audiences. That’s amazing considering the history he was working against, and we should expect to get some serious sandworm-riding in a few months when Dune: Part Two comes out. Will that movie manage to feel both like the competent production of its predecessor and the wildly imaginative messes that came before it? Is a Dune that isn’t a total boondoggle really Dune at all? No matter how good or bad it is, or how much money it makes, the specters of Sting’s metal underoos, Dalí’s functional dolphin shitter, and H.R. Giger’s Evil Orson Welles Planet are all looming above it, just out of frame, awakening the sleeping weirdos inside us all. (And possibly spawning even more sequels, which have to wrestle with the bugfuck other Dune novels.)

Leave a comment